“You don’t exist by yourself; you exist through the experiences you share with others”

Cape BURBERRY, trousers JEAN PAUL GAULTIER, sunglasses GENTLE MONSTER, necklace ASTERISK

Reanimating the art of opera, and making it cool again, may seem like a daunting venture. Luckily, STEVE KATONA is here to prove that the 400-year-old genre has a lot to live for in the present day—provided you’re mindful of outdated frameworks. A BERLIN-based singer, composer and performance artist, Katona masterfully interjects opera with contemporary arts, revolutionising both while simultaneously honouring their core principles. Whether it’s singing on the runway of a GMBH show or performing an experimental theatre piece at the TATE, Katona’s moving voice becomes a deadly weapon, and his vision, a thought-provoking, ground-shaking rebellion of the new generation. Enchanted at first sight, we had to catch up with the artist and delve into his process, discuss opera in the context of modernity, and hear about his upcoming narrative-based album.

Left—Trousers ACNE STUDIOS, shoes GUCCI, gloves PRADA, sunglasses TOM FORD

Right— Top WOLFORD, belt stylist’s own

Hey Steve! Let’s get right to it—tell us about your first encounters with music and how they led you to where you are today.

I come from a very classic workers’ family with no musical or artistic interest, but I’ve always had an urge to pursue these things with no ability to conceptualise them. I was weird growing up—I have these acoustic tics, so I always hum. I used to echo all the noises around me. Say, if the train was passing, I’d mimic the main frequency it was transmitting. Hearing classical music for the first time really resonated with me, and I started imitating it right away. I was in the choir for a bit and was also teaching myself the piano, secretly—so that my mum didn’t have to feel like she had to pay for it when we didn’t have money. My family supported me, but it wasn’t until my great-grandma stepped in to help me with financial resources that I pursued a musical education. From university, my story developed like a tree splitting into two branches—I wanted to sing opera, but also delve into contemporary arts. Now, I’m just shifting between the two worlds. When one is exhausting me, I have the other one to come back to.

The best of both worlds.

Sometimes the worst of both worlds as well, ha-ha. The world of classical music is a very institutionalised and strict one—there’s always something standing in front of you. Opera means that hundreds of people are involved in a show. Imagine I was a horrible diva causing drama—one person can ruin a piece so many put effort into. So, there is this reasonable spirit of protection that sometimes can turn into fear, leading people to forget the values an institution in a democratic country should represent. Despite that, the art itself is wonderful and is the reason I do it. The people you meet are amazing. The strength I find in contemporary art is in the fluidity—you don’t need to wait for things to happen, you can just make them happen yourself. I never thought that way in the context of classical music. There are many things happening outside the bubble, and sometimes it’s healthy to emancipate yourself from certain structures.

How does the relationship between these polar opposites— if you view them as such—manifest in your work?

For me, it’s like two sides of the same coin. In my practice, I mainly work as a vocalist, but I also want to compose. It’s usually me singing, composing and playing the instrument. Obviously, my abilities on an instrument are not nearly at a professional level. They’re good, but my biggest skill is my voice. So, I intermingle my own expertise with more unconventional sonic structures—like including electronic music or modifying certain instruments. A lot of it is also collaborating with different artists that bring a new point of perception.

What’s a memorable example of such collaboration?

The performance at the BOURSE DE COMMERCE in PARIS with BILLY BULTHEEL—a composer, performance artist and the person who introduced me to the art world outside of my studies. The show was a beautiful mix; we had musicians, instrumentalists, a singer and electronic sound, in which you could move and progress. Because it was taking place in an art gallery, it combined many different aspects into one melting pot. Another memorable collaboration is the opera Zelle, composed by JAMIE MAN, in which I sang one of the main roles. She created sculptures of light and mist, moving through shadow and music, asking questions that delve deeper than the nature of language could ever allow. It’s a beautiful opera unlike any other.

It’s so impressive how gracefully you intertwine core elements of opera with contemporary arts while melting the boundaries of both. Is experimentation at the centre of your process?

It depends on what you define as experimentation. My approach to music has always been a very natural one—it sank deeper under my surface without me even realising it. After some time of reflecting and intellectualising, you start bringing more complexity into it. For example, I’m a countertenor, which means I sing in the realm of an alto/mezzo-soprano—the highest male voice, largely associated with BAROQUE music. In those times, there was a phenomenon called castrati—male voices who sang main roles. They were the people castrated before puberty so that their high voices would remain—

—the lengths these institutions would go to just to preserve their oppressive structures! So laughably pathetic.

Exactly. Just to clarify, I’m not castrated—I use a different technique, ha-ha. So, you can imagine baroque music as a skeleton— you have nodes, let’s say A B A, and part A gets repeated. You use this skeleton structure to ornament it, which is called coloratura. The second time around, you sing A differently, essentially improvising it. There are rules, of course, but you have very high artistic freedom overall. From this comes my love for improvising—you can change certain notes based on how you think they relate to an emotion you want to portray. You can take this technique into many different situations even in contemporary art. It teaches you to not have an absolute concept of music.

Trousers ACNE STUDIOS, gloves PRADA

Speaking of artistic freedom, let’s talk about Hypatia. What inspired you to start composing your own opera piece?

I received a stipend for composition, and I’m now in the process of writing the opera. The story is about a Greek philosopher, astronomist and mathematician who lived in ALEXANDRIA and taught at the MUSEO UNIVERSITY—where the term museum comes from. HYPATIA was one of the only female philosophers in the late antiquity we know of, teaching natural sciences in an all-male space in a sexist society. She also developed a very sophisticated technology used for measuring stars. At the time, Christianity was growing and gained a lot of power—enough for a Christian mob to kill Hypatia. There has always been this fight: knowledge and critical thinking against those obeying arbitrary rules without questioning their truth. The latter impose thoughts on others because they feel entitled. History is mainly written by men, so many of her records disappeared through time and the tragic fact is that everyone knows her for being murdered, but not for her achievements. Of course, she is portrayed as a very beautiful woman and was very much romanticised as a person, but not as an academic.

We have such a warped perception of women’s contribution to society—and history in general. Women are often either objectified or disregarded as an accessory, and it’s so important to divorce these associations from their accomplishments and impact.

Exactly. For me, she is also a symbol of opposing those who try to keep control of people’s beliefs. Even now in Germany, the fascists are growing again, which is based on this anti-scientific and anti-pluralistic worldview; or in times of the pandemic, when people tried to threaten doctors and scientists who literally tried to save everyone’s lives. The oppression of women’s rights in Iran represents the exclusion of certain groups from education—

—and they said ‘groups’ make up over half of the population.

There are still so many people blinded by their ideology. For me, it’s threatening and was the main reason why I started to think about this story. I also wanted to adopt a scientific view on it as well. We think of time as being linear—something that has a starting and an ending point, which, in physical terms, is not true. Time has different speeds—on Earth, it’s slower than further away from the surface, as time is related to gravity. The higher the gravity, the slower the time passes around it. So, the basis for the project is two people from different times coming together, Hypatia representing antiquity and a protagonist from modern times. I don’t want to say too much, but there’s also a lot of criticism—it’s showing the same ongoing fight these people have in their respective worlds. I wanted to emphasise that we still need to care about it today: just because we have aeroplanes and electricity and think we’re an advanced species, these crimes are still happening.

Jacket, trousers and shoes MAGLIANO, shirt MORDECAI

Within this dynamic, what’s the power of music for you?

Music carries a lot of emotional value since you can’t touch it— music reaches people in this non-physical way. It has a very ethereal quality and resonates with everyone differently. Unlike many things in the contemporary art world, you can’t exactly sell it directly. It’s an invisible thing that is very present—whether you’re in a theatre or alone in your room listening to your favourite sad playlist after a rough day. It has the power of catharsis; it changes people to reflect on their own lives and encourages them to see the world differently. To me, this is very powerful.

The strong presence is very palpable in your work. Your voice has such a trance-inducing quality—and a certain darkness too. Is that intentional?

I’m a very melancholic person. I’m not necessarily sad, but often things bother me to the extent that I get angry and frustrated. Music has always been a way for me to find words for things I have no vocabulary for. I speak three other languages, and music is still the one I’m most comfortable with. There is definitely a sense of trance in my own music, but also melancholic tendencies. I’m not a scientist, but I feel like there is a connection there—personality somewhat shapes the voice, at least in the way I sing and emphasise things. Strangely, when it comes to the countertenor timbre, my expression indeed has a darker undertone.

What are some of the biggest challenges you have come across on your path?

Not going totally nuts moving between creative realms and making a lot of compromises within this movement. In contemporary arts, I find that I’m more comfortable operating within structures that are often more fluid. It’s hard to maintain my branches and nurture them similarly while providing each with the unique energy and dedication it requires.

Sounds tiring, but very much in alignment with your values.

I’m very value-driven. It’s very difficult for me to swallow things down when I think someone is wrong. It has caused a lot of trouble in my life, and it will continue to do so. At the same time, I also understand that I shouldn’t instantly turn away from things that don’t feel a hundred percent right. If every artist did that, the art world would look very different.

Left— Full-look MAGLIANO

Sadly, there’s often a certain trade-off you have to accept to w achievements?

I’m really proud that really good friendships have crystallised out of all these years of collaborating with different artists. It’s also about realising that you’re not alone in all these fights—I’ve always felt very alone, being so opposed to everything. Sometimes you doubt yourself for reasons you deem internal, but they actually turn out to be external, as other people live those realities too. After that, comes artistic achievements, like singing in the ancient theatre of EPIDAURUS for a festival in GREECE. It was breath-taking. Still, it’s not necessarily my achievement as you always achieve things in collaboration with others. All the lovely friends, supporters and allies is what makes me proud. I can do what I want and always find the spark in people, learn, and find inspiration from others. You don’t exist by yourself; you exist through experiences you share with others. This is what gives me strength.

What do you see as the future of opera? The perception of it as a dying art seems to be the dominating one among younger generations…

For centuries it was driven by misogyny, racism and exclusion— it’s simply a fact. This wasn’t eradicated completely in the last 30 years, but I think they started to reap the fruit of their own arrogance. There is progress. I don’t know if it’s a willingness or a lack of choices, but I know it’s a positive thing. Opera only has a future when it reinvents its structure while finding ways of representing the craft and tradition. Everyone knows it. In my assumption, opera might split: there will still be traditional opera houses, but a part of it will grow into a slightly different scene. If opera doesn’t adapt, it will just get even more exclusive.

It’s like a vicious cycle that can only be broken by a radical change in the system.

Exactly. There are already funding cuts all around Europe, and there will be even more I’m afraid. So, it will depend on private funding from people who will have a say in what should be played. It would be really sad for those actually involved and passionate about classical music to not have any opportunities simply because of the mismanagement of the past. So, there is a future, a very uncertain one. It’s like a ship that doesn’t know where it sails. The music will survive, but how it will be played is written in the stars. Perhaps we should ask Hypatia.

Opera embodies so much history, technique, discipline and feeling, but it all becomes more and more irrelevant the longer the establishment tries to cling to the rules of its crumbling past.

Most houses are extremely old institutions. Many processes of decision-making remain behind the curtains—it’s not particularly egalitarian. Now, it has to be challenged. For example, the #MeToo movement has also reached opera. More and more women are finding themselves in well-deserved positions of power. Casting is moving towards a more diverse direction. People are fed up. Ten years ago, after a funding cut, people would go out and protest. Now, no one cares. Making this art form relevant again is the biggest challenge.

And on a final note, what does the future hold for you?

I have plans that go in the direction of classical music. And I’m intending to go to VENICE next year. I want to finish composing my opera and find a venue to play it in. I’m also working on an album, actually. I use my singing and extended vocal techniques, like polyphonic singing originating from CENTRAL ASIA and MONGOLIA— when you sing two tones at the same time. The album will also have throat singing and narration of stories. I will also introduce elements that sound like electronic music but actually aren’t. I really want to show that one voice has many possibilities and to create a melting pot of different cultural practices and artistic ideas.

Right— Cape BURBERRY, sunglasses GENTLE MONSTER

Words by Evita Shrestha

Photography by Tristan Rösler @ Shotview Artists Management

Styling by Illia Kulishov

Hair by Aline Jakoby

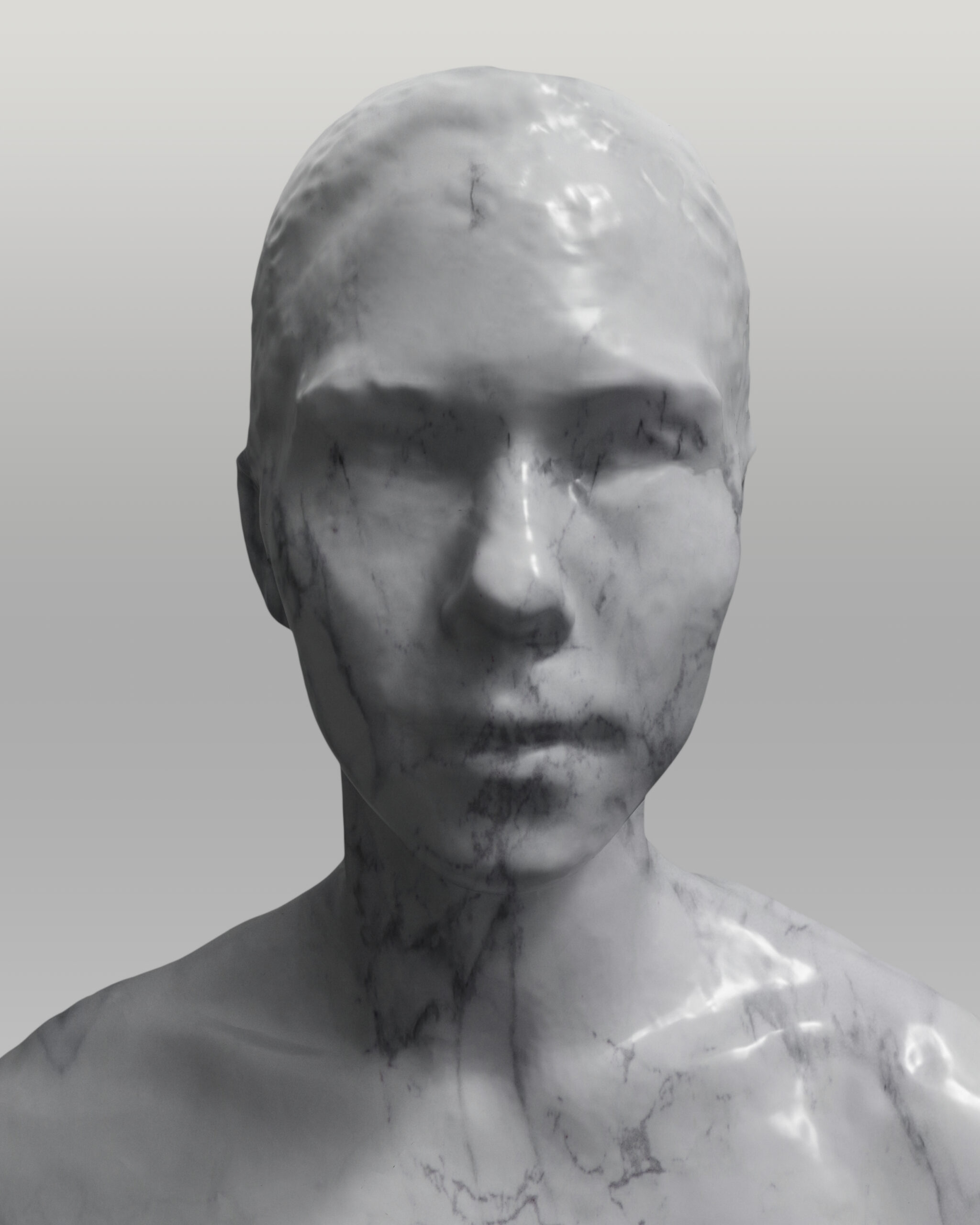

3D Visual effects by Leo Romanski

Post-production by Grain Berlin

Styling assistance by Delfina Giacovelli

Digital assistance by Kane Holz

Notifications