“If I see my painting and it leans too much into, ‘Oh, those women are so empowered,’ I want to stray away from it. I want to go for something more pessimistic”

Amanda Ba, Triumph, 2022, oil on canvas, 190 x 170 cm, courtesy of No Place Gallery

AMANDA BA’s paintings will inevitably perturb you—but it’s impossible to look away.

When I FaceTime Amanda Ba, it’s already 11 p.m. in CHINA. Ba is in HEFEI for the summer, a large city in the east of the country where she spent the first five years of her life. Laying on her stomach in a dimly lit bedroom, she apologises for the connection issues: “I think my Zoom account is linked to my US number so it still requires a VPN.” Throughout our conversation, the bedroom is periodically illuminated by the hallway light as the door is pushed open by a family member who wants to ask her a question (in Chinese). Each time, Ba laughs a little before answering patiently. Even through Zoom, there’s a sense of warmth and ease that belies the intensity of her work and her studious approach to theory.

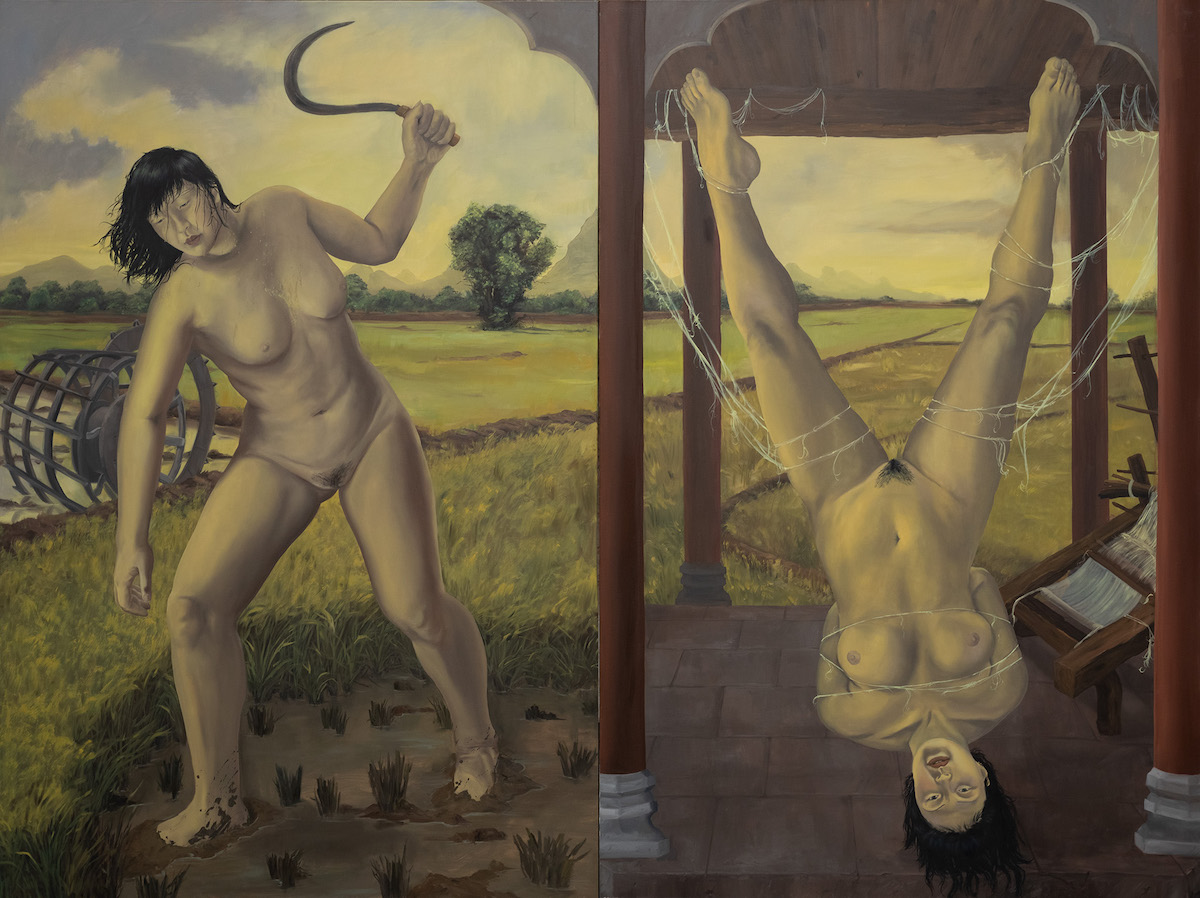

Raised in OHIO, the Chinese American artist has been painting since she was in high school, and is best known for her large-scale, psychologically disconcerting paintings that depict unsettling scenes of oversized naked women and brutish dogs that touch on themes of postcolonialism, Queer theory, posthumanism and critical race theory. Drawing from cultural academics, Ba has previously cited the likes of MEL CHEN, IEN ANG and DONNA HARAWAY as influences, with the title of her last solo show, The Incorrigible Giantess, inspired by a 1975 lecture by FOUCAULT. In it, the philosopher explores societal deviance, analysing the paradox that those society deems most in need of reform are also deemed beyond redemption. Ba depicts her interpretation of these subjects as colossal East Asian women who can be seen fighting, smoking and reading in strange, dystopian worlds. Uncaring and unaware of the viewer, they’re naked but not nude; we are not invited to stare at or sexualize their bodies but rather are witnesses to an awesome and mythical scene.

Amanda Ba, I-71, oil on canvas, 150 x 150 cm

It’s seemingly obvious that Ba is a big reader, so it’s surprising to find out that, bar the occasional dip into MAGGIE NELSON’s The Argonauts, she’s not reading anything at the moment, joking that she’s having an “illiterate summer”. “There’s just so much to take in in China, I’m too overstimulated to read any theory right now,” she explains. Inevitably, we end up talking about Barbie instead. Amanda says that despite the “blatant lack of intersectionality”, the film is doing some good in China, where the culture has become progressively more heteronormative of late. “On Chinese social media, there’s this whole thing where girls are taking their boyfriends to see the Barbie movie, and how the boyfriends feel about it is a green flag test. As in, if your boyfriend doesn’t storm out of the theatre, then he passes the test,” she explains. It comes at an important time: famous trans TV host, JIN XING, has been pulled off air after years in the public eye, and in 2021 the country issued a ban on ‘effeminate’ men on TV, blurring out the earrings of male celebrities.

Looking at Ba’s paintings, it’s impossible to imagine these giantesses occupying any world in which women might be seen as dolls to be played with. Her works both reject traditional notions of femininity and challenge conceptions of the submissive Asian woman. In the Giantess series, the figures are naked and blocky but Ba says that she doesn’t want people to confuse her work with some kind of body positivity agenda: “If I see my painting and it leans too much into, ‘Oh, those women are so empowered,’ I want to stray away from it. I want to go for something more pessimistic.”

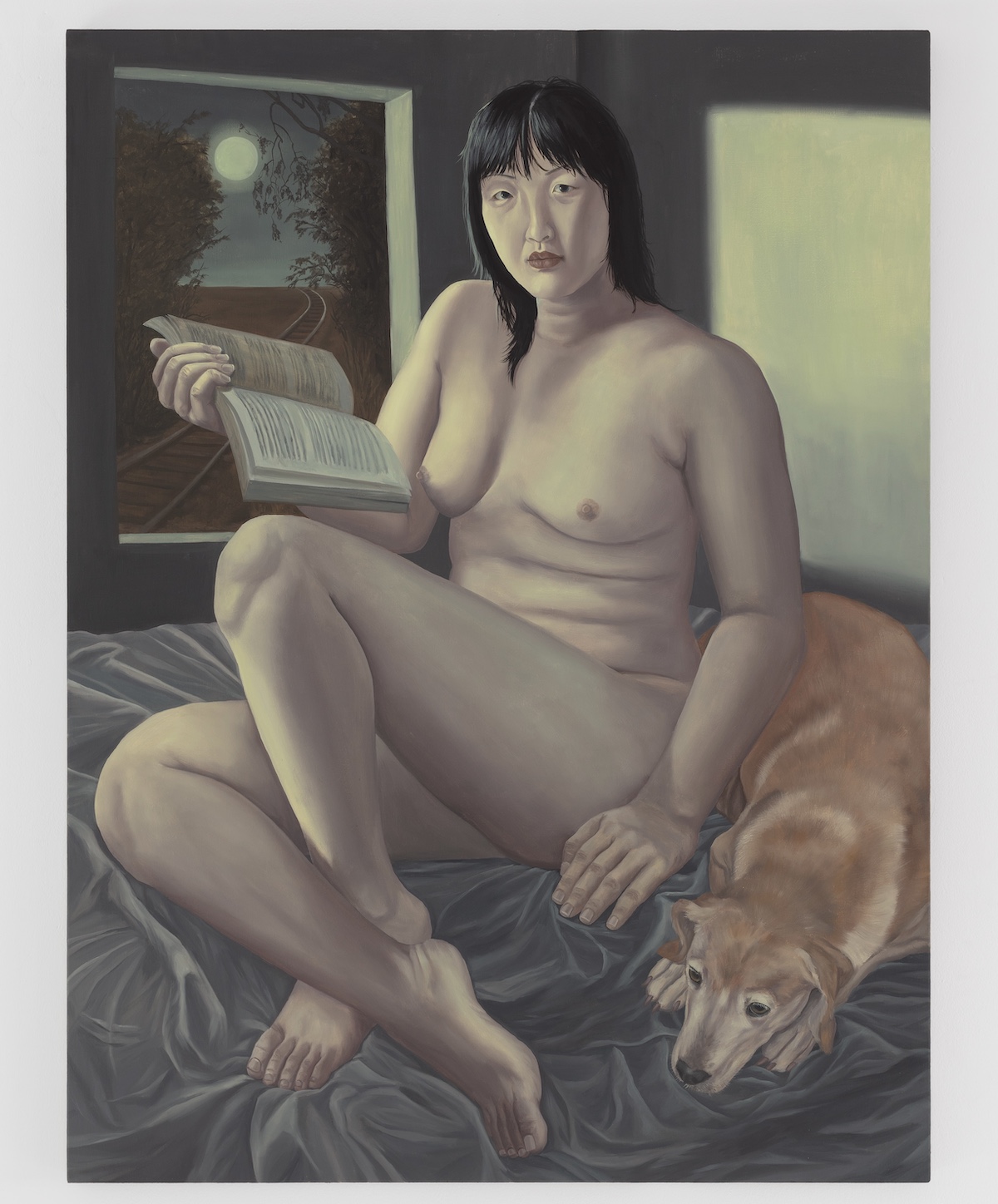

Amanda Ba, Giantess Reading (Self Portrait), 2022, oil on canvas, 120 x 90 cm, courtesy of No Place Gallery

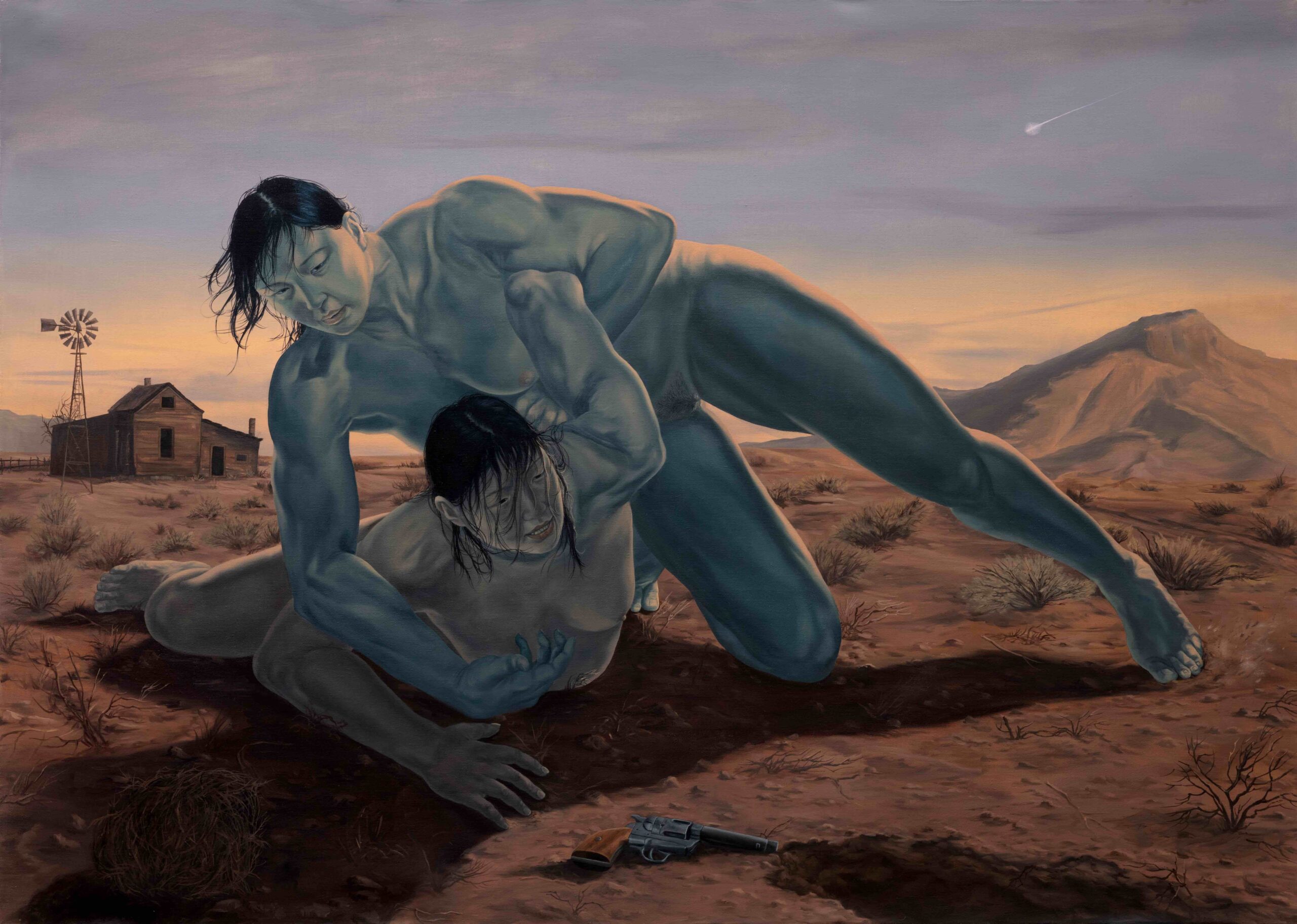

Though her paintings may be disturbing, the women in them are rarely disturbed. Instead, they are unabashed, powerful and occasionally cruel. In Triumph, one red woman stands atop another, crushing her with her feet on both breasts. A cigarette dangles from her left hand as she looks down at her victim. The composition was inspired by a religious piece of a saint vanquishing a devil, and the longer you look at it, the more you cringe in vicarious pain. Disturbing and complex, Ba’s works are also preoccupied with Queerness, the psychosexual and what it means to be post-human. These may sound like mere buzzwords for an exhibition catalogue, but the uncomfortably captivating works speak for themselves. In The Incorrigible Giantess (2022) a group of oversized women and dogs are caught mid-battle, tinged red as if bathed in the glare of a stop sign, fighting it out in a dusty Martian landscape. As with most of her paintings that feature dogs, the lines between animal and human are blurred: “I wanted it to be like a Greek frieze and very primordial, in which [the scene] could be either prehistoric or post-apocalyptic,” she says.

It’s notable how often the West features in the backgrounds of Ba’s paintings—in the most ‘wild, wild west’ way possible. It’s all dirt roads, tumbleweed and houses on prairies. In Giantess Reading, an abandoned railway stretches out through the window, and a dilapidated barn creaks in the storm of What is Home to a Giantess? in which a red woman on all fours occupies the foreground and, on the porch, an American Bully dog howls at the wind. The giantess’s pose could be construed as sexual but it’s impossible to project any eroticism onto such a scene. “I was thinking about these very lonely landscapes for this painting, I might have looked up a picture of [artist] ANDREW WYETH’s house for the piece,” she confesses. “I knew he was from PENNSYLVANIA which, like Ohio, is a bit rural and random.”

Amanda Ba, Bitch and Bull, 2021, oil on canvas, 100 x 100 cm, courtesy of No Place Gallery

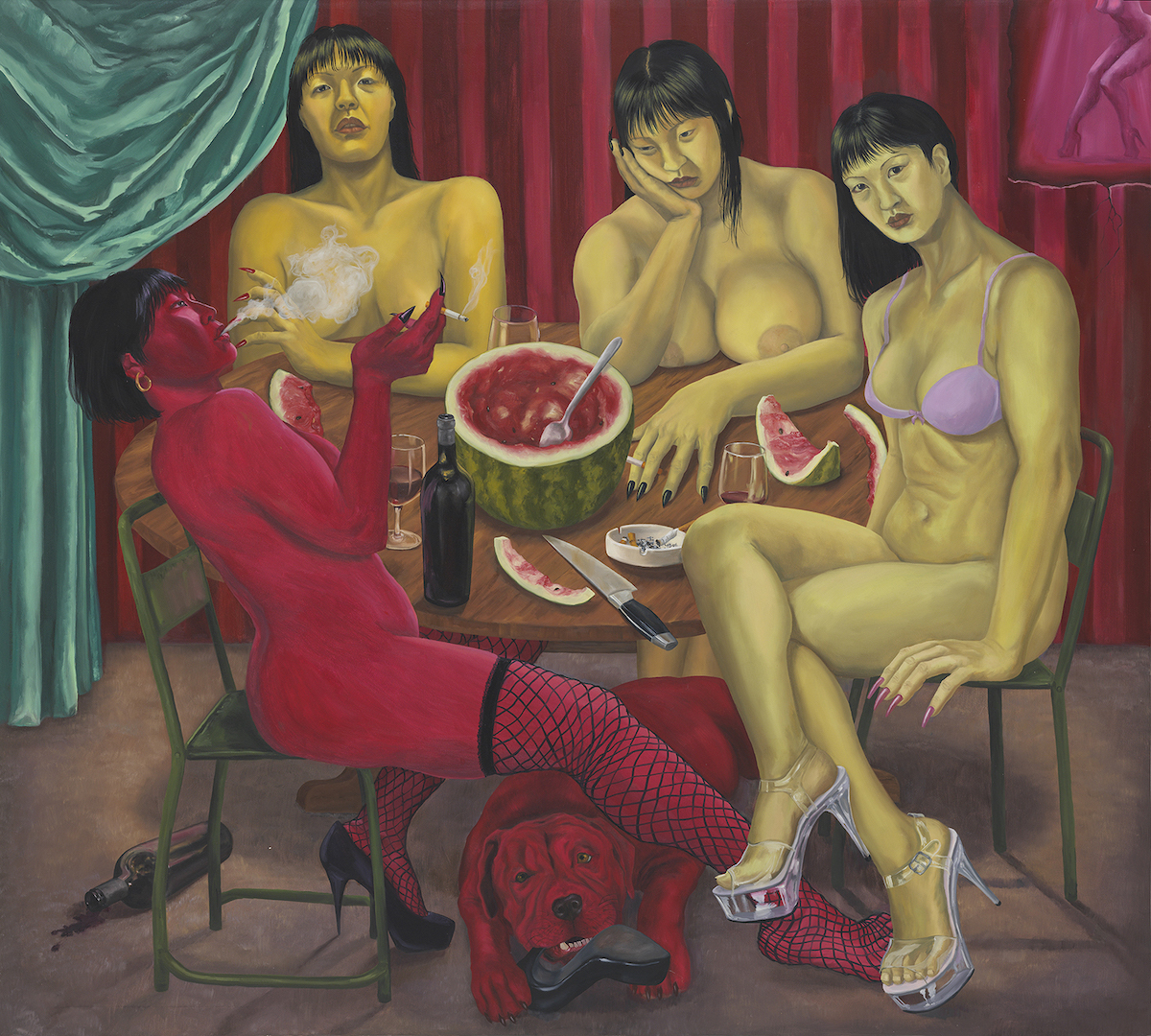

Amanda Ba, Four Sisters, oil on canvas, 190 x 170 cm, courtesy of No Place Gallery

Ba is exhibiting next. “It’s funny because Ohio and Hefei have a lot of parallels. For one, they’re internationally recognised as sister cities and equally, they’re both big places but neither of them is necessarily the nexus of anything. Everyone has a family member that’s from there but no one wants to visit or live there. People from Hefei want to go to SHANGHAI and people from Ohio want to go to NEW YORK,” she says, laughing.

Ohio, it seems, lacks glamour—but the artist is taking advantage of the opportunity to explore its stories and in some ways, place it on the cultural map. Ba will be exhibiting four large paintings in September but this time around, the figures will be clothed in order to ground them in a very specific reality. “I’m just taking ironic scenes of growing up in the Midwest so one has cheerleaders on a track field, then in another a girl rides a HARLEY DAVIDSON on the highway past a billboard in Ohio that says, ‘Hell is real’. Then there’s a girl wearing camouflage walking through the forest with a deer,” she says. “Ohio is a very strange place in terms of American culture because of its averageness; it has everything that the entirety of America has averaged into a state and it’s also a swing state politically. Something I find interesting is the Asian diasporic experience of middle America— these are not typically places with a Chinatown or a long history of Asian immigration. If you’re in middle America, chances are most people who immigrated there did so in the last 30 to 40 years. It makes for a very specific diasporic experience.”

We discuss the various subcultures that exist in places that do have a history of East Asian presence. There’s California’s Bay Area, with a second or third-generation Asian population, wealthier and deeply integrated into North American culture, as well as the more working-class community in New York who have long resided in QUEENS. But Ba says there are no such enclaves in the Midwest: “In Ohio, the community is geographically scattered. There’s not so much a sense of a distinct Asian identity, which ends up leading to white assimilation. And it also leads to a lot of the Asian population becoming upper middle class and Republican. Tons of Chinese Midwesterners are big Trump supporters because they don’t feel connected to any sort of racial or oppressive struggle. They just see their money and their assets. That very specific diasporic experience primes kids towards white assimilation, so that’s what I find interesting.”

Amanda Ba, American Western, 2022, oil on canvas, 215 x 150 cm, courtesy of No Place Gallery

Watermelons, like dogs, are a recurring theme in Ba’s work and are one of the ways that the artist explores the cultural and racial tensions of her surroundings. In Watermelon Girl, a giantess with thinly arched eyebrows and red lipstick sits on a red-and-white chequered blanket with her knees up. In front of her exposed crotch, a scooped-out watermelon sits with a spoon extending out of it. “The watermelon’s longest and most obvious racial history is with black people, right? During slavery, watermelon was a very cheap and fast-growing fruit, so it became really popular in the South with slaves, which led to racist connotations of the fruit, that’s one aspect of it. Another aspect is that in China, watermelon is a staple of the summer diet and it’s something I’m familiar with and associate with communal eating. In China, you would never buy cut-up watermelons like white people. You buy the whole thing and you share it,” she explains.

In the companion text to the Giantess exhibition, Amanda writes an essay entitled On the Sterilization of Watermelon, tracking the fruit’s journey from a symbol of slavery to freedom to the sanitized, seedless place it holds in white society today. “The watermelon is an important fruit across the various collective imaginations of people of colour, for it carries a complex, oppressive history and a charged symbolism. Besides being a fruit of celebration, it is also associated with a long history of marginalization,” she writes. The popularity of seedless watermelons in white America is a symptom of an attempt to sanitize the fruit, robbing it of the seeds that Chinese people believe give it its flavour and sexual connotations. The placement of it next to the giantess may be an attempt to reclaim the narrative, the seeded and halved watermelon as incorrigible and unownable as the sexuality of the woman consuming it.

Both I and other journalists have repeatedly referred to Ba’s work as “unsettling”, and I ask her what she thinks of the word. “I think ‘unsettling’ is cool. They’re not meant to be very comfortable images—nor are they meant to be easily legible. I hope ‘unsettling’ encompasses that they’re not beautiful to look at and that people don’t know how to feel at first. If you don’t know how to feel about it, you spend longer looking at it, which might mean that [people] are ultimately more invested in the piece.”

Amanda Ba, Quantum Desire (Lightning’s Longing), oil on canvas, 200 x 200cm, courtesy of No Place Gallery

Amanda Ba, The Plower and the Weaver (diptych), oil on canvas, 180 x 240 cm, courtesy of No Place Gallery

Amanda Ba, Titanomachia, 2022, oil on canvas, 170 x 300 cm, courtesy of No Place Gallery

Words by Tiffany Lai

Images courtesy of Amanda Ba & No Place Gallery