In conversation with the filmmaker, Sophie MacCorquodale

Trigger warning: This interview discusses topics surrounding sexual violence

A conversation with Sophie MacCorquodale is never dull. As a London-based documentary filmmaker, photographer, and artist, Sophie’s work defies the confines of popular culture. Her diverse portfolio spans collaborations with everyone from traditional fashion brands such as Gucci, Chloe, Moschino and Givenchy, to following heavy metal band Slayer on tour, to filming the quietened rooms of The Rhyl and District Labour Club in rural Wales. Yet, at the core of everything she does remains a constant: a dedication to unveiling authentic narratives, going beneath the surface to discover forgotten stories. In my chat with Sophie, we journey through the evolution of her creative path. From growing up in the 80s in the northwest to her early experiences in an old folks home, Sophie shares how these moments ignited her fascination with human connection within confined spaces, laying the groundwork for her exploration of societal constraints.

Her most recent documentary is a poignant extension of this human-focused perspective, delving into the lives of survivors of sexual violence and examining the role of medicine and psychiatry in their journeys. In Sophie’s own words, “For me, it’s always about supporting the underdog, the underrepresented, the curious, and the alternative.” Initially fueled by frustration with the lack of space and support for women in the fashion and production industry, Sophie collaborated with trans activist Lucia Blayke on this documentary addressing the complexities of sexual violence. Commissioned by the SHaMe research project at Birkbeck University, the film serves as a powerful platform for survivors to share their experiences.

Hi Sophie! Can you begin with a brief introduction about yourself and your work?

Hi Gracie! I am an artist, filmmaker, producer, photographer and hair colourist. My work has largely sat within the world of popular culture and fashion but is increasingly turning more towards social justice and what it means to be part of an intersectional feminist movement — visually, politically and conceptually.

Was this creative path one you always envisioned for yourself?

To be honest, if I went to a better school I’d probably be an anthropologist. Alas, growing up in the 80’s in the northwest, my first experience of work was at an old folks home. I can still vividly remember the old people and being fascinated by how they interacted with each other in their confined spaces and the stories they chose to share. I guess in some ways that’s always what my work has been about, asking: how do we escape from a brain (and a society) that we are largely locked into?

In telling these stories, your films have become increasingly about diving into offbeat, underground or taboo subjects. What’s the magnetic pull of these narratives for you as a visual storyteller? What makes them click with you?

For me, it’s always about supporting the underdog, the underrepresented, the curious and the alternative. How do we escape personally and collectively; be it on holiday in a shit seaside town in Wales, as fans of the thrash metal band Slayer, or in drag on the dance floor at Sink the Pink. What does it mean to be human and find a space, a moment in time, or an experience that resonates with you beyond the daily grind?

Given this approach, how did your draw to the untold lead you to take on this specific project?

This was quite a development from my work around the underground. I was working quite a bit in fashion and production and got increasingly frustrated by the lack of space and support for women. I was also working with Lucia Blayke, who is a trans activist and genuinely inspirational woman. She set up the first LGBTQ+ strip club in the UK, Harpies and founded London Trans Pride. We were trying to get funding for a project (that would be brilliant) but struggled to get any monetary support. Seeing how hostile branches of feminism are made me sad, and so in beginning this project, I wanted to do something that was very firmly rooted in intersectional feminism ideals. By that, I mean, just supporting other women, as you can guarantee all have experienced misogyny — not just from men, but from other women too, as that is how society is set up. Anyway, I’m rambling…

I like the ramble! Please continue…

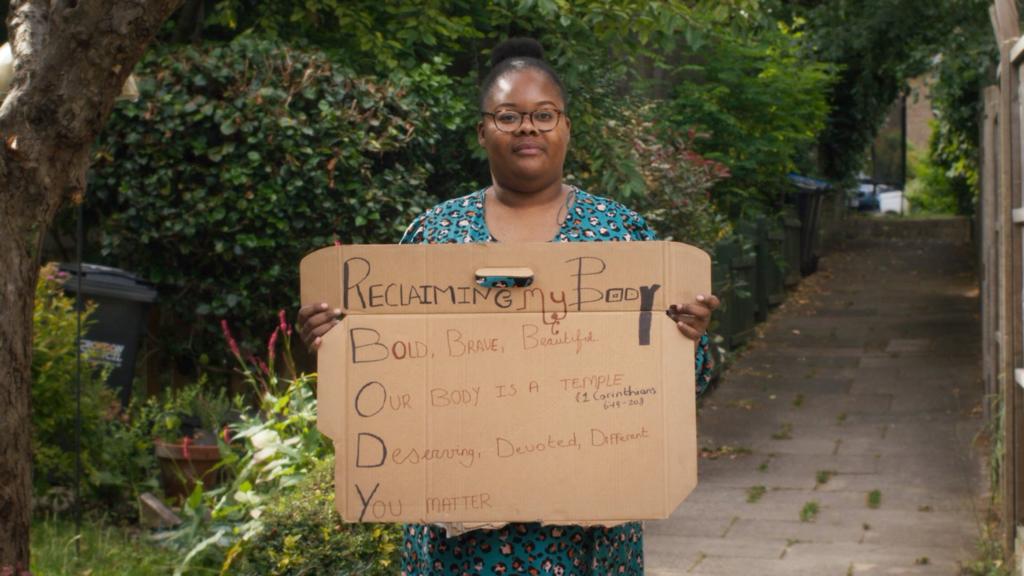

I got approached by SHaME, a research project that explores the role of medicine and psychiatry in sexual violence at Birkbeck University to tender for a documentary. The rest is history. My focus became on creating a safe platform for survivors of sexual violence to share their experiences of survival and the role that medicine and psychiatry did (and didn’t) play in that. My documentary shares four stories that hopefully resonate with a more inclusive narrative, as the current one in the media is still largely focussed exclusively on white women’s experience — but of course, lesbians, trans women, black women and queer women all experience sexual violence, however, getting the much-needed support for them often comes with many additional barriers. To be clear, I am a white woman, so it was important that the producers I worked with were from the communities that I represented and that I listened and learned. I read a lot and can recommend Joanna Bourke and Lucia Osborne-Crowley‘s work.

Before diving into this project, were there any nerves or second thoughts you experienced?

I was raped in Ibiza when I was in my 20s and I never shared that story. I guess my nerves were about the survivors trusting me with their stories and experiences. My discovery pretty early on was that it couldn’t be about labouring on their experiences but celebrating their immense bravery and the journey they are on, which can be a daily struggle. They are far braver than me and I think my main fear was surrounding how I do them justice. That all sounds very grandiose, but there is very little justice around sexual violence, less than 2% of perpetrators are convicted and a fraction of survivors/victims go to the police. So the survivors have been carrying the weight of what has happened around them for years and have to deal with that every day. I asked myself how I show that weight on screen in a manner that can support them, and others and address the shortcomings in terms of medical and psychological support. Alongside, starting a dialogue around how to care for all survivors that is survivor focussed. Essentially, what do they need?

Why was it important for you to capture the diverse and intricate journey of navigating life after sexual violence? What made this diversity of experience crucial for conveying the essence of the film?

All those involved in the project were very conscious of the importance of seeing their communities represented in the dialogue around what survivors need, where they can go to get help, what is being done and what needs to be done to support all survivors of sexual violence. Their support experiences were largely shit and the impact that has had on their mind and body has been long-term and detrimental to every aspect of their lives. If they could prevent that for others there is some meaning, purpose or comfort in their ordeal. Survivor communities are increasingly becoming important as people can’t access the professionals working in the field. I guess I wanted to represent them how they wanted to be represented and that was both my challenge and fear.

The post-premiere panel includes notable speakers and academics like Maisha Sumah and Joanna Bourke. How are their thoughts woven into the fabric of the film’s conversation?

Joanna Bourkes’ work in sexual violence research is unquestionable and she has been a massive support throughout the documentary. Her book, Disgrace, Global Reflections on Sexual Violence came out during the production and she was an amazing support in helping me put the narratives in a historical and global context. Also, it makes me address the trauma narrative, which has become the main approach to talking about SV in our context. However, what universalises the experience and the consensus from the academics at SHaME and Joanna is the idea that we need to centralise survivors’ experience in all aspects of care. People’s circumstances and experiences can not be generalised.

Maisha Sumah has gone through so much for somebody so young. When we first spoke, she asked where I wanted to begin and it was hard to identify what narrative we should go with when making a short documentary. Her advocacy work is incredible and she came to the Netherlands as a refugee from Sierra Leone when she was a small child and wants to trace her journey back to there. Maisha is a deeply spiritual person, and so because of this, her healing journey was different to other survivors, offering another discourse, as it was centred around spiritual healing.

As the film premiere draws near, what thoughts, feelings, or emotions are you experiencing in anticipation of sharing it with the world?

Can I get back to you on that after the event? Ha-ha. Currently, I am a bit overwhelmed about distribution, PR and how do we get this film out to the world with limited financial means?! However, if I dig a bit deeper I am feeling quite proud and I also feel a lot of love for everyone involved. This documentary focuses on one aspect of a much larger debate around the abuse of power, which feels like a conversation which is so inherent in every aspect of life atm. I guess the way to counterbalance that is to be part of a movement towards greater understanding, and allyship and to keep learning and asking questions. As a documentary filmmaker, I feel happy that I can do it.

Any projects/ events/ ideas in the pipeline you would like to share?

I have a few projects in the pipeline, but ultimately, at the moment I am very curious about the female gaze and sex. I believe it’s about minutiae details, consent and understanding, so I’m up for exploring that. I’ve also been working on a project about regional ideals of beauty in the UK, what the way we want to look tells us about the society around us, history and identity. There’s also one about female strength. So much to say and do… just need to find the funding

SHaME: Stories of Survival

Nov 29th, 2023

Learn more about SHaME here

Words by Grace Powell

All stills provided by Sophie MacCorquodale