Polaroid Rage

Resilience and power are synonymous with multimedia artist Slava Mogutin. The Russian born, New York-based photographer, author and all-around creative knows the struggle and the reality of the fight for his rights. Exiled from Russia after being condemned to potential prison time for two highly publicized criminal cases and then being the first to attempt to register for same-sex marriage, he officially filed for asylum in America. Today, Slava’s photography, as well as his multimedia work, has been exhibited all over the world, including MoMA PS1 and Museum of Arts and Design in New York as well as his latest exhibition, Polaroid Rage, which is currently on view at Galerie Kernweine in Stuttgart, Germany, and at Villa Noailles Art Centre in Hyères, France. Also, make sure to keep eyes and ears open for his upcoming show at Schwules Museum in Berlin “Intimacy – New Queer Art from Berlin and Beyond. We had the absolute honour of talking with Slava about his past, present and future creative voyages…

Could you begin by telling us about your artistry?

I started out as a poet and journalist in Moscow and ended up fleeing my country for New York at the age of 21. I was the first Russian to receive political asylum in the US because of homophobic persecution. In exile, I continued to write and also started focusing more on my visual art, with photography being my favourite tool of expression.

Your story is certainly one to remember. Would you mind talking through the journey leading up to where you are today?

Living in Russia was as challenging as leaving Russia, I had to reinvent myself both personally and professionally. It took me about five years before I was confident enough to start writing in English and publishing and exhibiting my visual art. My exile and immigrant experience informed everything I do across different media. However, my passion for poetry remains the same. I’m now working on a bilingual collection of poetry titled Satan Youth.

Of course, such experiences are undoubtedly prominent within your work. Does your photography take on the role of healing for you, or rather, a political statement? Or both…

I enjoy taking pictures and sharing my experiences just as much as I did in my teenage years. My first pictures were documenting the underground music scene in Moscow and St Petersburg, and ever since I see my mission primarily as a documentary photographer and journalist. For many years I refused to shoot in a studio, and I still take my best pictures in natural settings with ambient light, without any styling or directing.

What influence do you hope to create with such work?

Photography is a great metaphor for our life, it’s a confluence of light and darkness, details coming out of shadows. Photography has the power to transcend time and death and preserve the image for the generations to come.

Your latest exhibition, POLAROID RAGE, has been developing for some time now. Could you tell us about the concept behind the work?

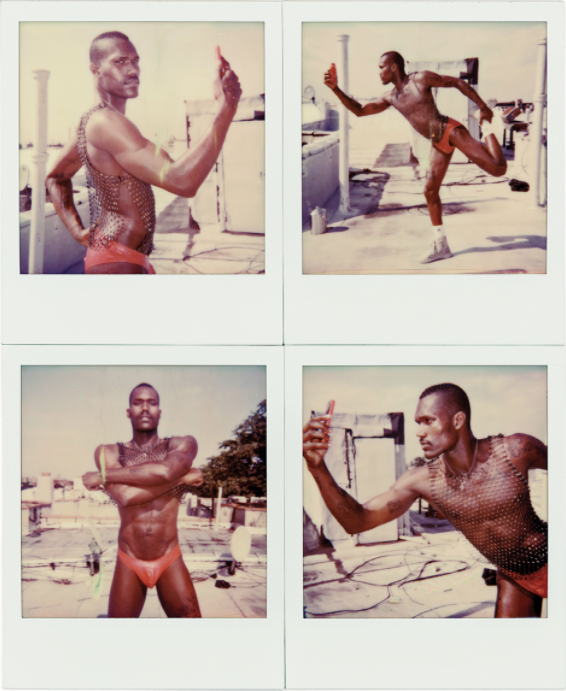

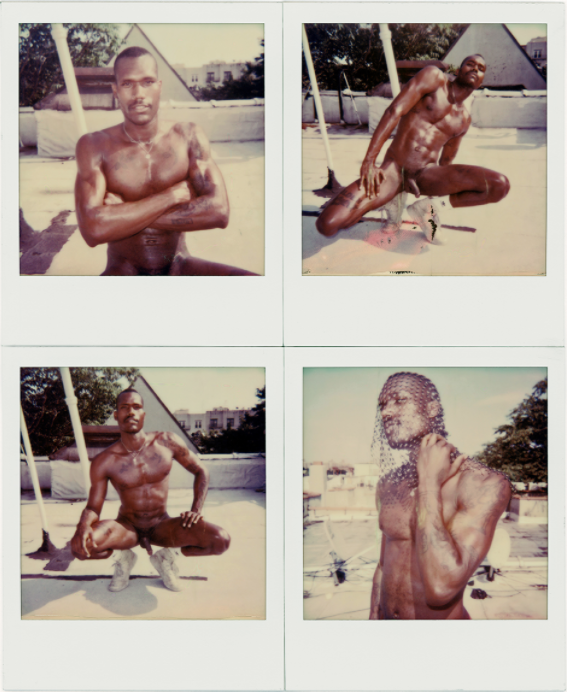

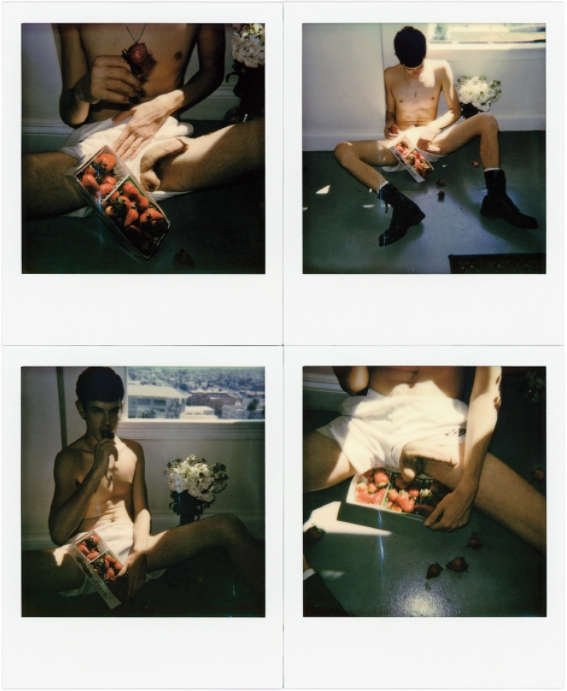

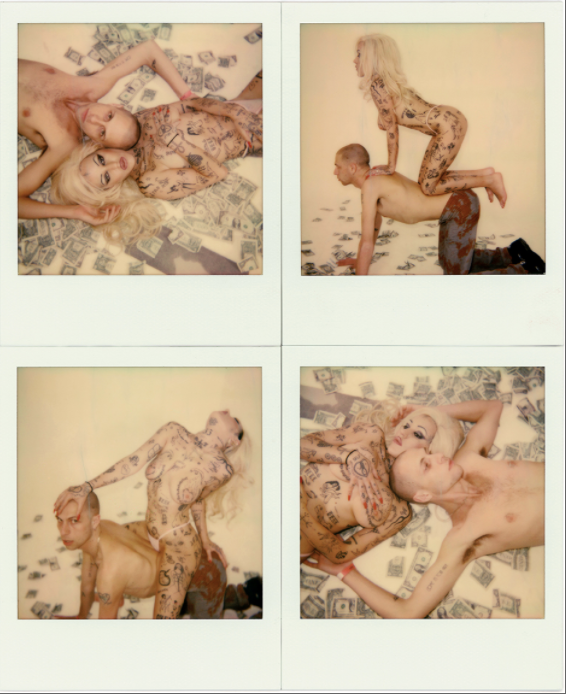

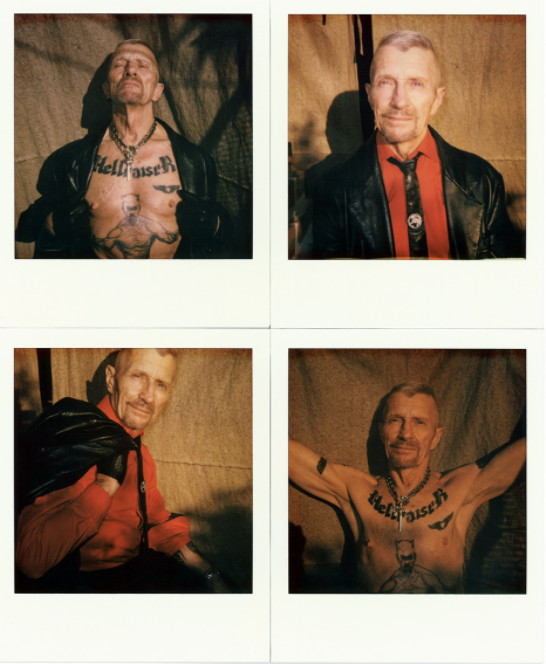

SM: I’ve been experimenting with various Polaroid cameras and formats over the past two decades. Back in 2013, I did a joint show with the queen of Polaroid photography Maripol. That’s when I started assembling individual pictures in the grids of four in order to create multidimensional portraits. Most of those pictures were taken in NY and California. In 2018 I gave up my New York studio and spent most of the following two years travelling between New York, Los Angeles and Berlin. My encounters and relationships are documented in this series, and it is still a project in progress.

Within this collection, I see an embrace, celebration and uplifting of individuality and uniqueness; is this something you base your imagery on, or something you aim to draw out of the subject?

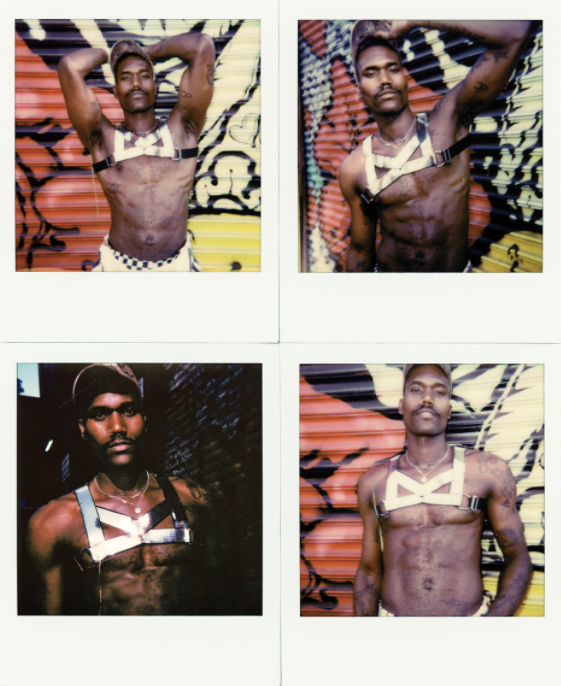

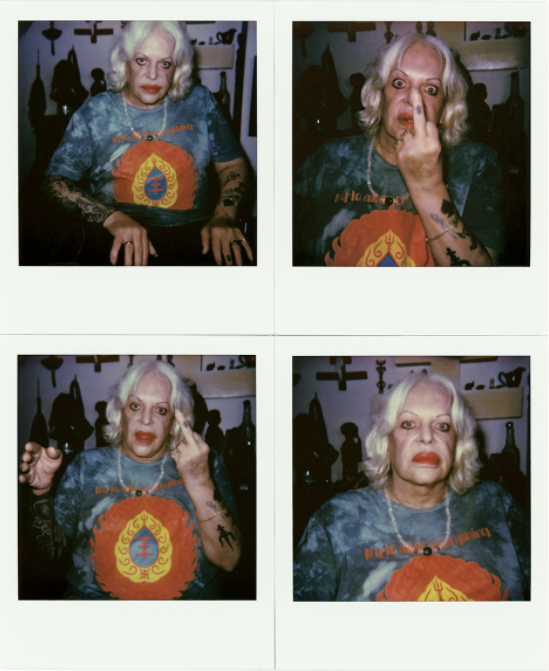

It’s a multinational spectrum of gender, sexuality, age and race. It’s a celebration of human nature and spirit. In the midst of the pandemic when the very idea of human connection, intimacy and sensuality is being examined and reinvented, I’m more than ever focused on the studies of the human form that highlight what we have in common, not what sets us apart from one another.

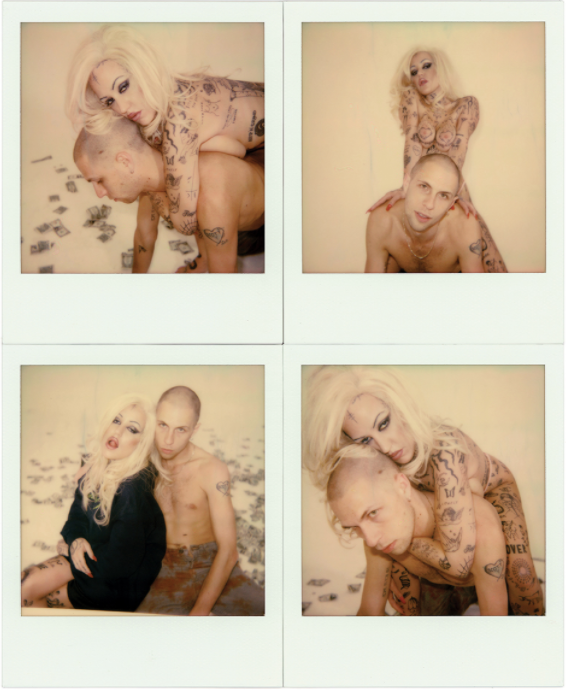

I love the Brooke Candy and Luke Abby feature! Here, and within many other pieces, there’s a nod to sexual freedom. How do you view sex, sexuality and the freedom to express yourself through these mediums?

I’m always fascinated by the human body in all possible positions and contortions. We live in an increasingly sterile, censored and oppressed society where the naked body is often seen as a threat. Sexuality is being marginalized and politicized, impersonal virtual interactions have replaced authentic human experiences. Being naked and sexual in front of the camera is a talent not everyone has. I admire people who can express themselves freely without fear and prejudice.

Your work predominantly captures and shares the perspective of a younger generation. Why is this important to you?

I identify with the younger generation because they don’t have as much ideological and cultural baggage as my generation that grew up before the Internet and social media. That said, it’s important to listen to those who came before us. I was fortunate to meet and become friends with many visionary queer elders—people like Allen Ginsberg, Quentin Crisp, Edmund White, Bruce Benderson, Gary Indiana, Dennis Cooper, and Genesis P-Orridge—and learnt something from each and every one of them.

What do you believe can be learnt from this generation?

You don’t have to subscribe to an ideology, religion or dogma of any kind. Think for yourself. Don’t let hypocrisy, censorship, political correctness and cancel culture control your life.

Notions of displacement run through many individuals within today’s world. What advice would you give your audience in dealing with these feelings?

Being a displaced person, an immigrant is a life-changing experience that gives you a certain angle and perspective on every fundamental aspect of life. It’s like having second life—you want it to be better than the last one that you escaped. Being an immigrant in Trump’s America, it’s not easy. I paid my dues to be able to speak my mind and address the evils of my adopted home country just as much as I talk about the evils of Putin’s Russia.

If we were to reflect on one thing within the collection, what do you wish it would be?

I love the intimacy and immediacy of Polaroid. It’s like a cross between the honesty of analogue photography and instant gratification of the Digital Age. You shoot the picture and if you don’t like it, reshoot it again. From my experience, sometimes the rejects are the best ones.

Your Polaroid Rage show runs until the end of November. What’s next?

More shows, more books, more art! Despite the restrictions caused by the pandemic, I was happy to take a break from travelling, take a deep breath, pause and reevaluate my work. I’ve been processing and editing my massive film archive and rediscovering pictures and projects from years ago. And I’m still shooting Polaroids and working on a book based on this series.

Imagery from Slava’s Polaroid Rage collection

POLAROID RAGE now on view at Galerie Kernweine, Stuttgart

19 September – 22nd November

BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL now on view at Galerie Kernweine, Stuttgart

19 September – 22nd November

Words by Grace Powell

Notifications