…. and the second summer of love.

Martine Rose stands for culture behind clothes. From her first experience of the British rave scene to her thriving, eponymous label that boasts cult recognition, Rose represents a playful approach to social commentary within design. The menswear designer has spent 15 years channelling the iconography of the masses into fashion. Her archetypes of counter- culture hold up mirrors to many, and showcase the remnants of our everyday wear: coin mark on the pocket, faded fabric, or a crumpled shirt sleeve. Curious to know more, Glamcult spoke to Rose about her creative growth, relatable characters and the importance of maintaining energy during Fashion Week.

Roots are everything to Martine Rose. So it’s no surprise: talking to the designer evokes a warmth anyone familiar with British counterculture recognises to be pride. A Londoner with Jamaican heritage, Rose has navigated the fashion circles of the city since her graduation. After founding her label in 2007, and receiving praise from early FASHION EAST, Rose’s work has since flourished to show the sharp references and technical design we know today.

Like most creatives with an umbrella of interests, it wasn’t fashion that Rose was initially drawn to. “Fashion was some- thing that happened in Paris on catwalks,” she explains. “It wasn’t something attached to my life. It was far too remote.” Pre-Instagram and the ‘democratisation’ of clothes, fashion operated in a sphere far from the place Martine Rose called home.

Instead, Rose grew up watching the hypnotic culture behind the clothes people actually wore. She recalls exactly when this began to crystallise. It was 1989— a year after the ‘Second Summer of Love’ —and it was the peak of British rave culture. As the youngest of a large extended family, Rose watched her older siblings get ready for nights ahead. Just nine years old and too young to join them, she became aware of this pivotal culture she wanted to be a part of: “I recognised how important it felt and knew that it was significant,” she recalls. “I was really into what people wore.”

For her older sister, this would be Moschino, Versace and BOY London. Paired with handmade creations like shammy leathers, she’d wear them out to carnivals or after-parties on Clapham Common. Rose remembers the impact of Jean Paul Gaultier through the more accessible Junior Gaultier: “That’s what transcended the catwalks and made it into streetwear,” she says. It was the brands with diffusion lines that resonated with young people, who were drawn in that typically British way to blend ‘high’ culture with ‘low’. At the heart of this lives an attitude of working-class flamboyance. “My granddad was a tailor,” Rose explains. “He would never go out any less than completely put together.” Which calls to mind another familiar British trope: it’s as normal to get dolled-up for a pint in the local as you would for Fashion Week.

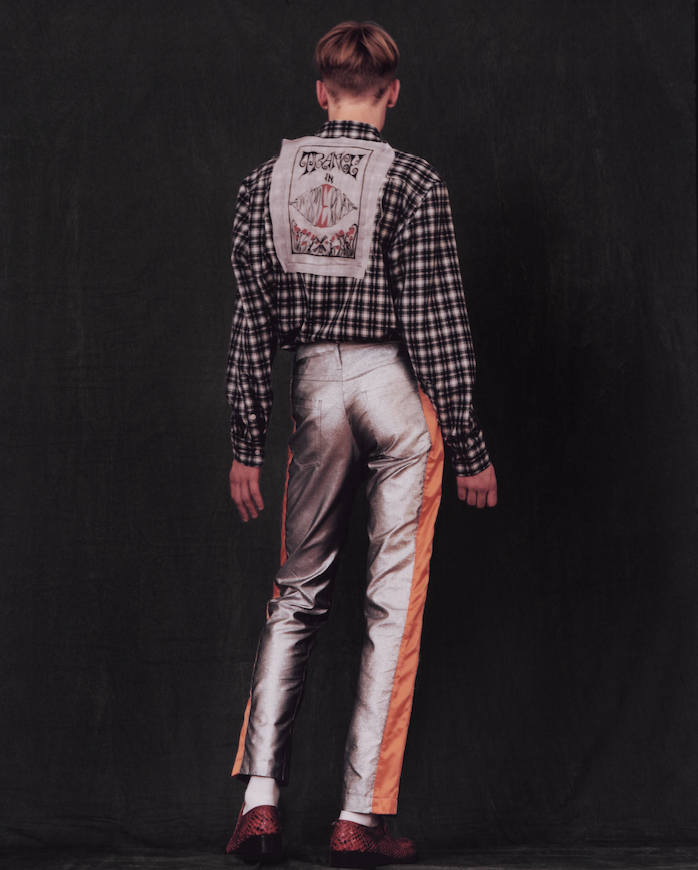

Blending culture is a typical outcome from such a class-based society as Britain. One which appears all Queens-tea from the outside, but secretly brews up the SEX PISTOLS and THE CLASH. Blurring the lines between what is ‘popular’ and what is ‘respectable’ has to involve the rupture of classist stereotypes. Rose’s de- sire, even now, to “fall somewhere in the margins” of these arbitrary divides takes energy from the ambiguity embedded in punk and early rave: “What was different, subversive and political about it was a lack of defined uniform. Especially between the genders, it’s all very blurry and the norms are broken down.” The remnants of this time resurface in Rose’s collections like a subconscious residue: “It was such an important point for me,” she says. “Everything circles around that time. But it’s not like it goes up on a big mood board. It’s just a thing that manifests every time that I design.”

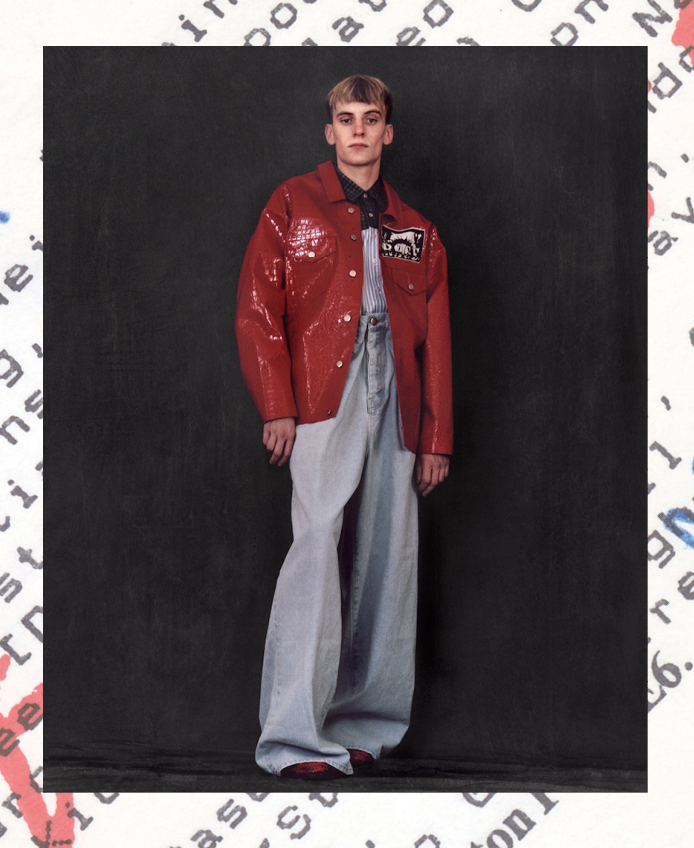

That observant eye has become an act of documentation. Rose constructs us a mini-history of the football hooligans, skinheads and rude boys. While the original wearers could have been your uncle or brother, they were also key figures within sub- and countercultures that the designer was drawn to. “I’ve always looked to those people on the edges. They’re the people I want to hang out with, they’re the people I’ve always found most inspiring.” The influence certainly shines through. Rose has built resonant portraits of con- temporary masculinity in disproportionate trackies, bomber jackets and white Nikes. Like an upturned, tailored wardrobe department on the set of This is England, the designer has framed the epoch in a way that captures the eclecticism of the times

For SS21, Rose turns her observation to the here and now. Inspired by the work-at- home Covid-19 era, she fashioned a collection about our intimate relationships with interior space. In particular, she explores the ways of maintaining sexual expression in shared space. The characters too have been updated for our times— from a hypermasculine city banker with straining shirt buttons, to the garter-wearing football coach with lycras to match. You can also forget about tropes of menswear; Rose brings back gender fluidity through the art of the 21st-century power-dress.

While Rose isn’t sure what effect holding up the mirror has, she senses it gives people the comfort of familiarity: “I like to make the ordinary extraordinary on some levels. That means a lot of people can recognise parts of their own life, their own character or their history in bits.” It’s a common thought, that fashion reflects our identity, but one which becomes powerful upon acknowledging that collective identity is culture. The reciprocity of this relationship is what sustains Martine Rose, given that the cultural side of fashion was what she was drawn to in the first place: “It was the cultural aspect that I was interested in,” she says. “I wasn’t pouring over Vogues when I was four or five, [but] I was looking at magazines such as The Face and i-D, or music magazines like Mixmag.”

The ability to walk in the culture/fashion hinterlands is even more apparent during Rose’s shows. She often presents in unconventional locations, bringing the Fashion Week audi- ence closer to spaces where communities actually live. “I want to open the conversation so that it extends beyond this pampered, privileged audience,” she says. In 2016, Rose showcased at an indoor market in Seven Sisters, an area of North London with one of the city’s most multicultural populations. Asking all the vendors to stay open, she invited the audience to indulge in the mix of foods from Cuban to Brazilian. The onlookers included locals who watched from stallholder’s chairs while getting their scheduled acrylics or blowouts. She reminisces: “Those people were whooping and shouting. It was like a party to them.”

Being so influenced by wearable clothing, squeezing into industry constraints has meant some compromises along the way: “Most designers are frustrated by the rhythm and the structure of it be- cause it doesn’t reflect us and how we live,” she explains. We joke about whether anyone actually has a seasonal wardrobe, and the designer sighs, thinking about the arbitrary categorisations of sea- sons and trends. “The model is so old-fashioned, it really is… but it is the structure that exists and we have to fit into if we want to sell.” Yet, if there’s one thing Martine Rose has carved in the industry, it’s a place where you can celebrate the type of fashion that makes you think. “I’ve always felt like I don’t mind if people hate [my work]. I do mind if people feel indifferent.” Even if her work is met with dis- dain or discomfort, ultimately that’s where the emotion comes in: “I’m not interested in good taste,” she says. “I’m interested when I’m not sure what something makes me feel. That’s what I look for in myself. It means that I’m occupying a space.”

After all, it’s the reflections on ourselves and the spaces we occupy that are essential to understand- ing the collective cultures we build. Rose likens this process to MAYA ANGELOU’s poem And Still I Rise. “Even though that’s speaking about a very specific experience of being a Black female, it can speak to a wider experience of what we go through as a global community— that there’s always hope, strength and creativity.” It’s a powerful message to finish on, that in troubled times creativity can breed cultural insight.