“I am a totally narcissistic victim of my own brain.”

Female Figure (2014). Mixed media Overall dimensions vary with each installation. Photo by Jonathan Smith, courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner, New York.

With part one of Jordan Wolfson’s solo show at the Stedelijk having just ceased, its sequel is now ready to be exposed. Employing motion technology, the artist brings more of his part seductive, part terrifying animatronic creations to Amsterdam. TRUTH/LOVE boldly questions pop culture and the gaze, relying heavily on the reaction of its spectators. Find yourself face to face with a witch-faced, hyper-sexualised robot in an obsessive cycle of watching and being watched. Sitting down with Glamcult, Wolfson divulges his reliance on instinct, his pursuit to invert titillation and his battles with confidence.

Throughout your work there is a recurring presence of the gaze, both from the audience to the object and vice versa. You have previously mentioned the importance of this “bridge of connection” in relation to the gaze. What is it you find so interesting and important about this?

If you look around, you can see all of these works have eye contact. It activates something between object and subject, which I think is really interesting. For one moment you’re looking at something sculpturally and objectively, and then you’re forced to look at it subjectively. It inverts and distorts the viewing experience. For me, I feel that eye contact allows a more fluid flow of content to travel, indiscriminately. It actually opens something almost non-judgementally, an informal bridge that anything can travel over. That’s what I experience personally—I can’t say this is true for everyone.

Tell us about what inspired you to begin making animatronics! Is it true that Disney influenced you?

Disney didn’t influence me as such. I had seen an animatronic at Disney world—I could’ve seen it anywhere—and it had this amazing physicality to it. I’m a bit embarrassed about it really because everyone always says, “I hear you were influenced by Disney”. [Laughs] I saw something; I saw movement and I became infatuated with it. And then I saw more animatronics and I became equally infatuated with those. So it was just this first encounter, and it went from there. I wanted to transport the physicality that I found so moving into my work because previously I had only been making videos.

Continuing with the idea of the gaze, there is a blink moment with both Female Figure and Coloured Sculpture. What is the idea behind this?

It’s at one point a kind of pause in the frequency and at another, a kind of device to increase the illusion of life.

Female Figure (2014). Mixed media Overall dimensions vary with each installation. Photo by Jonathan Smith, courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner, New York.

Female Figure has two juxtaposing sides to her: the conventionally ‘perfect’ female body with long blond hair and the horrifying bird mask for her face. What are you trying to say about her by doing this?

That’s a really formal thing that is happening. Her body is the sexual object but then, how do you invert titillation? I thought using a witches mask would work, as a witch is the symbol for infertility, which suggests that her body is infertile—it’s an infertile image. When you have opposites, it’s like two opposite magnets; they create a friction and tension between them. That’s the same with the eye contact for Female Figure. The reason why only two or three people are allowed to see her at a time is because then you experience her looking away and then she looks at you. You feel this scare (at least for me I do); it’s like a gear, a cognitive dissonance gearshift.

You use a distorted remix of Robin Thicke’s controversial Blurred Lines to accompany Female Figure, followed by the repeated cryptic phrase: “My mother is dead, my father is dead, I’m gay, I’d like to be a poet, this is my house”. What are you trying to convey with this audible language?

It was very intuitive. Initially I thought the piece would be this robot screaming, “This is my house”. I thought it was kind of a clever institutional critique, but then it just really didn’t work that way. I found the phrase “My mother is dead, my father is dead, I’m gay, I’d like to be a poet, this is my house” really compelling and interesting to start with. It then goes into a poem for the mother, talking about having sex with your mother and the animatronic says, “When you look at yourself you’re ugly, when you touch yourself you’re hot, I’m getting old, I’m getting fat and I don’t believe in God.” I was obsessed with this and the idea of believing in God. I kept questioning myself, is it bad to say that? It was all fiction. I’m not gay, my parents are alive and I don’t want to be a poet. It’s not me, this is fiction, I’m like an author and I’m writing things, but whatever comes out of me, you hear it and see it—that’s my shape. One day the dialog just dropped into my mind, like this list, so I wrote it down. I thought of certain things that I thought would be compelling or interesting that the sculpture could say.

You say you always work intuitively. Are you not seduced to dissect that intuition?

I really try not to be. I am a totally narcissistic victim of my own brain. I meditate all the time and try and clear my head. I focus very much on my own consciousness; I focus on the quality and health of my consciousness. I really believe that professional success comes from creative success and creative success comes from this consistent maintenance of consciousness and prescience.

Have you ever been surprised by your own creations, or how people have responded to them?

I was surprised that people had such a strong reaction to them because I don’t have that, but that is partly because I made them. Female Figure receives a stronger reaction than most because it is just very intense in person. There were times where it did scare me. I remember being alone in this warehouse where I was working on it and it literally looked up in the mirror at me, right in the eyes. I ran out!

What made you separate the exhibits into MANIC/LOVE and TRUTH/LOVE?

I looked at all the spaces at the Stedelijk and felt like this space worked best for my work so I just proposed that we do two shows. I think it gives it more of a statement as well.

Both MANIC/LOVE and TRUTH/LOVE display a fascination with pop culture, especially through the music you reappropriate—in the sense that it’s removed from its usual setting. How do you choose this music and what are you hoping it conveys?

The songs I choose are almost involuntary, it’s instinct. Then I also think from a more intellectual standpoint that there is something radical about direct appropriation. You are literally just taking something. I love Kenneth Anger’s Rabbit’s Moon; there is something radical about simply taking a song and looping it or taking a song and starting or finishing it in the wrong place. There is radicalism to its bluntness, radicalism to its simplicity.

When it comes to your work, what’s your best dream and worst nightmare?

My biggest nightmare is not being able to figure it out compositionally. Maybe that’s a weakness of mine; I shouldn’t care and should be more innovative. I would be more innovative if I wasn’t such a coward who is so obsessed and over-preparing. [Laughs]

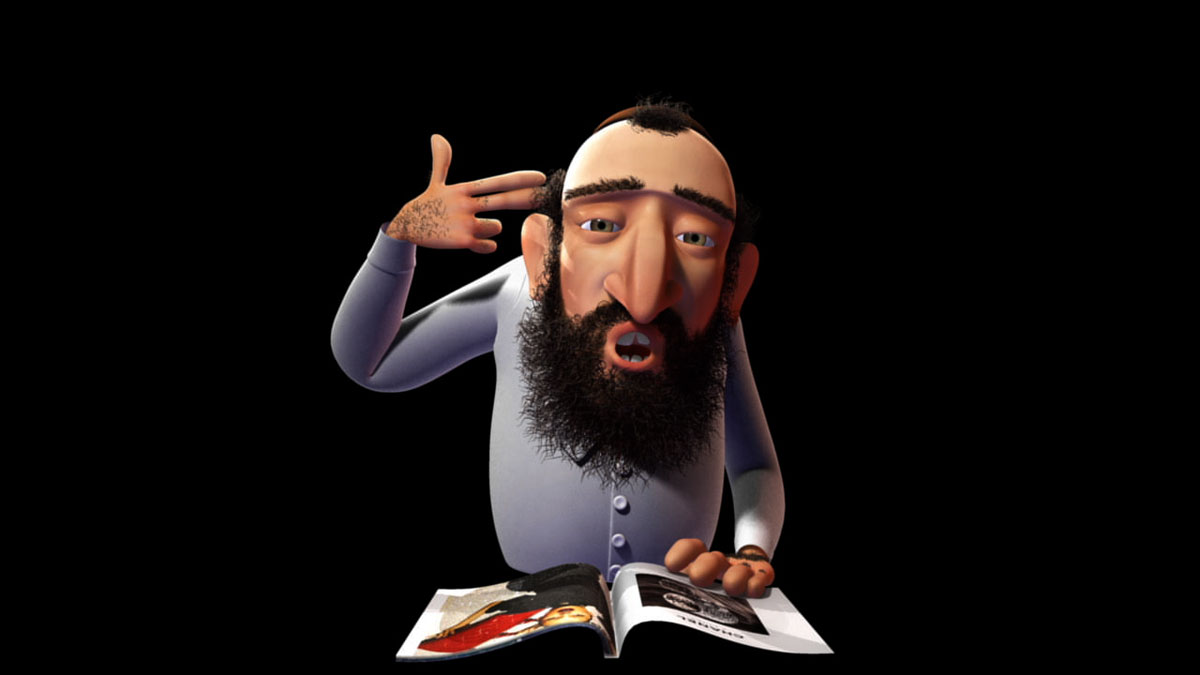

Jordan Wolfson. Still from Animation, masks, 2011. Video animation on monitor, 12:29 min, color, sound Overall dimensions vary with each installation. WOLJO0014/ Courtesy the artist, David Zwirner, New York, and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

TRUTH/LOVE

18 February until 23 April

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Words by Lottie Hodson

Notifications