Modes of expression and representation

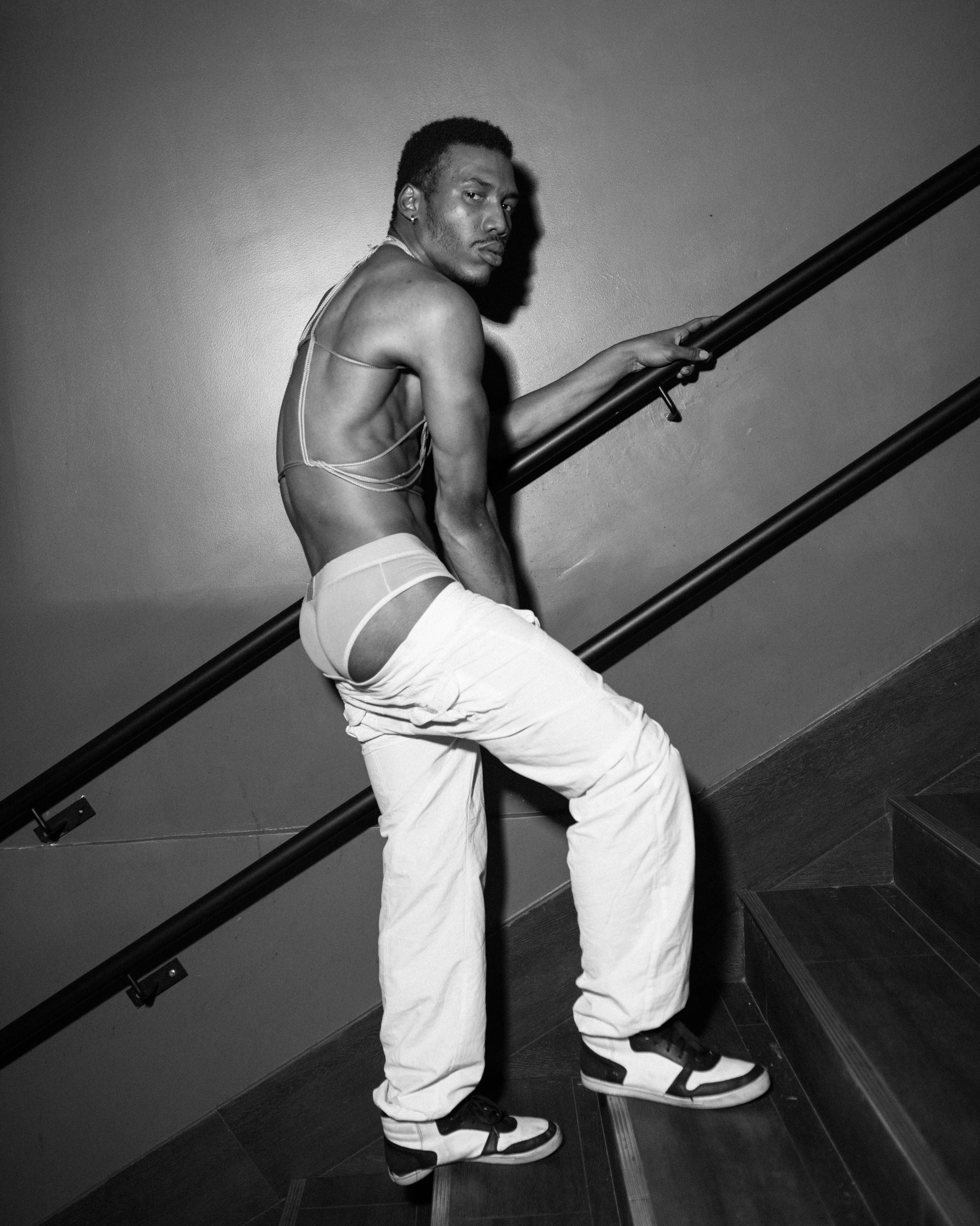

Representation and healing are the pillars behind Dustin Thierry’s momentous portraits. From building personal relationships to entire communities, Thierry shares his message of love through the deep embrace of his camera lens. Born in Curaçao, raised in the Netherlands, his work explores the experience of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora as well as documenting queer nightlife in Europe. He’s collaborated with some of the most infamously fabulous characters of the Ballroom scene, as well as the familiar faces of Amsterdam’s underground for solo exhibitions at Aperture, Foam and Rencontres Bamako. He’s been awarded the Berry Koedam Award and the prix du public award at the Hyères Festival, and continues to tell a story of hope and community through his work, creating a platform for those who need to be heard.

Our journeys through life often impact the work we produce. How has yours shaped your creativity?

I was born on the Caribbean island of Curaçao, which is a former colony of the Netherlands. At a young age my parents got divorced and my brother and I travelled with my mother to settle in Hilversum. Through circumstances, my mother wasn’t able to financially provide for us, which ultimately led to her sending us back to live with my father in Curaçao. At 14 I left the island once again to attend a boarding school in the Netherlands. These very early life experiences significantly shaped my world view and this therefore shapes my work; it has made me sensitive to the humanity of people, modes of expression and representation. These are all themes that appear in my work—consciously or subconsciously. Next to that, I believe that there is uniqueness in the universality of things and people. I believe that all beings are equal and should be treated as such.

Do you therefore see your work as more of an external or internal expression?

When I read books or watch films or view other types of art, I always look for emotions and a hidden internal world; these are things that are mostly experienced on an invisible level and are not always to be found at face value. These experiences are what I try to capture with the medium of photography within the subject that I photograph. I would rather that my work be felt than directly explained, and I am waiting for the day they develop film that can also directly transfer the emotion of the moment the photograph was taken, so the viewer can feel what was felt at that specific moment in time.

Your art centres around the Afro-Caribbean diaspora in the Netherlands, a subject simultaneously personal to you and shared by many. Do you feel your work reflects a more personal or universal experience?

I cannot speak on how my work evokes a response in others or what it achieves on a larger scale; that is not my place to say and that is also not my aim. My goal, however, is to represent the Afro-Caribbean diaspora, and this is who my work is made for in the first place. If this can help connect and heal people beyond that, I am very grateful.

Connection and healing are prevalent within all of your work. But particularly visible within your work documenting the Ballroom community…

I am humbled by the kindness and grace of the Ballroom community and wiser than when I first began.

You always appear to emphasize this kindness first, subsequently creating beautiful portraits.

While I acknowledge trauma is present, I refuse to let myself, my work and the people in it be defined by it—because they are still people and their experience extends beyond that narrative alone. I make a conscious choice to uplift and celebrate instead of placing my people and work in the narrative of victimization and helplessness, which the white gaze more than often does.

Withdrawing from this narrative could therefore invoke a sense of healing?

Healing is the essence of my work, next to representation. And in some ways, these two go hand in hand. When you see yourself represented, you can find connection and, possibly, community. And it is my belief that within having or finding a community lies healing.

Could you talk me through your latest series? Emphasizing representation, inspiring change and critically evaluating contemporary debates are important themes here.

My latest portrait series for Nederlands Fotomuseum portrays photographers of colour, a group whose existence is being ignored, in particular in the (Dutch) world of photography. In contemporary debates around diversity one can often hear the complaint: “But we can’t find them.” This series shows that they are here and that they have a right to be here. Photography, or any other visual medium, can be a powerful tool in terms of representation. [Photography] can affirm something which was not visible at first, or something you did not know you were missing. It can also aid in helping you find something you were looking for. Since portraiture in my work falls under photography, this is my philosophy.

The role of dialogue also seems to play an essential role in this series.

There should be a more urgent and pressing dialogue on who gets to represent what narrative and to have a deeper look and critical conversation, which is often a painful one, on which narratives are currently being upheld and how these need to be broken down to create space for new ones.

What can you tell us about your ongoing series, Opulence?

Opulence first came to fruition in 2013, when I was connected to Amber Vineyard, mother of The House Of Vineyard. She was the one to organize the first Ballroom events in the Netherlands. This was the spark that made me realize that I wanted to create a project that would address issues of representation, exoticism, toxic masculinity, the importance of safe spaces and family structures. That specific urgency and depth emerged from the death of my brother, who never experienced such a community, but had a deep yearning for one.

Would you consider your art to therefor be inspired by building this community for him?

When someone commits suicide, there are so many questions: Why did this happen? Why did they do that? What could I have done differently? What could I have done to take his pain away? Why didn’t we see the signs? In most cases, there is no absolute answer. Just a huge empty space. I was immensely sad knowing that, because of his whereabouts, he could not obtain access to a community which could have provided him with a safe space, a shelter. This is my homage to the journey that should have been his and beyond.

A homage which not only plays tribute to your brother, but also the scene.

I went into the community with all these questions, and along the way found peace that this was the place where he would have found a home and, hopefully, would have felt less lonely.

The theme of the magazine is RISE; how do you perceive a ‘risen’ world?

On a personal note, I believe that my job isn’t solely to photograph scenes and present them, but also to actively use my platform and voice to give back to those who need their voices to be heard.

Words by Grace Powell

Photography by Dustin Thierry

All images from the Opulence series ©, Dustin Thierry, courtesy of the artist.

Notifications