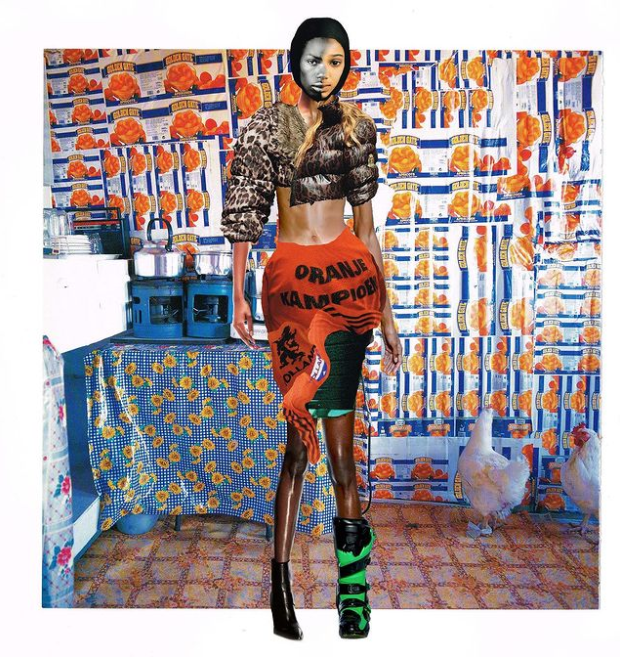

Presenting The Rebound Parley, Denzel Veerkamp engages with his cultural experience in the Netherlands as a person of colour. Playful yet powerful in its message, the collection translates profound research alongside a personal exploration of identity, resulting in a moving body of work with many layers to be explored. In light of the FashionClash x Glamcult exhibition, we caught up with Veerkamp to talk about the narratives behind his collection, his childhood love for Ajax, his way of re-using textiles and the importance of education to move forward to the post-colonial society.

Hey Denzel! How are you?

Feeling quite well. I just came back from Fashion Week, so I’m still calming down a bit after all these social gatherings. It’s not exactly overwhelming, but just a lot of trying to leave a good impression.

Let’s begin with yourself and your journey in fashion.

So, I’m 26 years old, I was born and raised in Amsterdam, and I got my bachelor’s in Fashion Design studying in Rotterdam at Willem de Kooning Academy. Actually, the minor I took – the 6 months before you go into the graduation process — really helped me to pinpoint some of the thoughts I’d had for a while. It was a course in Cultural Diversity. It was a lot of literature which resonated with my struggle with my cultural background and growing up in the post-colonial setting in the Netherlands. It really helped me to build a foundation to transcend all of those emotions into a collection. I also got so many conversations and reactions out of that, and now I just want to continue that translation through clothes.

Your graduation collection proposes a critical view of your experience as an individual with a dual heritage in ‘the post-colonial Netherlands’. Could you tell me more about this and also how you’ve made this visible in your work?

My mother is from the Netherlands, and she’s white. My dad is from Surinam, a former Dutch colony. It’s two contrasting worlds. Apart from all the literature, I also conducted interviews with people who grew up in Amsterdam but also have Surinamese descent like me. One conversation was with my mum’s best friend from back in the day, and we talked for like three hours about institutional racism, but also about other topics like the football club Ajax. It sort of forms a familiar refuge in a way. Growing up, it was super normal – a boy loving football should be an Ajax fan. It’s one day of the week when everyone’s cheering for the same thing – everyone is proud of being an ‘Amsterdammer’. I’ve always felt like I wasn’t really welcome here, and also never felt like a worthy Dutch citizen. But that way, at least I could feel like I’m proud of my city, of my club. Looking back at it now, it’s super weird, and toxic, haha.

Definitely. But at that point, it must’ve been good to have a sense of belonging.

It’s a community for sure. But it’s also a bit of a hate-love situation, and something that is interesting for me to dive into. To see what the emotions are – what the good feelings are, what the bad ones are, and how we can improve situations like this. Being a bridge in the middle of two worlds. There is so much polarisation in the world, so I want to explore what I can do to connect people and make them understand each other a little bit more. I sometimes disagree with one group, and it’s like ‘I get where you’re coming from, but you just need to listen.’ I feel like sometimes, that helps more than just saying “Black power”.

Making a collection voicing all these concerns is very much something to be proud of. Coming back to Ajax and how you made this bridge physical, you incorporated the Ajax symbols in your pieces, right?

Yeah, it was the Ajax shirt from season 2005/2006, and I had it as a kid. I love this shirt so much, and it’s so nostalgic for me to see it now. I transformed this very masculine standard fitting football jersey into a dress and it gave me the power to express the way I feel. I just wanted to charge it with some new energy.

And take away that toxic masculine narrative, I imagine.

Exactly.

Would you say we do live in a post-colonial country? There is a lot more that still needs to change.

It’s quite a complex topic, as it is post-colonial in a literal way, but certain systems are still there. For instance, one of the techniques I applied in my collections was putting out a ruler on all the post-consumer garments and cutting them. Not thinking about the end result, just putting the pieces together. During my whole research into the African diaspora, I stumbled upon the Berlin Conference of 1884 pretty quickly. I’ve spoken to so many people about it, and no one knows about it. It was when European imperialist regimes decided to divide the whole continent between each other literally just using a ruler. You can imagine the huge disruption that still persists today. History has always been my favourite subject, I knew all the tiniest details. But the fact that I was never taught that at school is just a very big example of how badly we need to decolonize the education system and become aware of certain systems that are being held in place.

Education is the first step, and we’re not even there yet.

It’s a good example of how we are not really post-colonial yet. It’s crucial to understand the history of how we all came together here right now in order to understand the future of tomorrow.

Besides reflecting on your experience, your collection has also critiqued the Fashion Industry’s destructive habits, and you teamed up with the Salvation Army to produce the body of work. Could you tell me a bit about how this came to life?

I approached them and they were really interested to see what I wanted to do. They wanted to listen. We collectively decided that I could pick out the disposed of items, like the ones with holes or broken zippers, or just bad quality. Items like these usually are shipped to Eastern Europe, and from there they go to Africa to be a burden there. It’s frustrating to see this cycle, so I wanted to jump in and see what I could do by demonstrating how much worth there still is in the garments that we throw away. Not to criticise anyone’s practice, but there are loads of people upcycling now, and sometimes I feel it’s not really a solution – if you use things that are nice anyway.

When did you learn that all these items were shipped to Africa?

I just wanted to know what happens to all the things that are seen to be worthless. I also wanted to see if I could develop a sort of new fabric by pressing all the disposed of fabrics together. I was super open-minded at that point. On a deeper level, I saw clothes that are ending up in Ghana and form huge landfill sites. It’s really heart-wrenching to see that. There’s even a term for it – Obroni Wawu meaning, ‘the white man is dead’. People across Africa just get the leftovers. I wanted to make that system of fast fashion visible, combining this with my technique of making my cuts with a ruler, it was a very direct link to point out how Africa is being treated. As a Western society, we try to make everything look cool but it’s really not.

It’s consistently not acknowledging the history and the consequences of our actions.

In Holland, we have this attitude that we’re very tolerant, very sober and open. I have this look with a curtain; it’s static, and to me, it’s like a statue. It has this superior arrogance that I witness on a daily basis. But then, there is this rain jacket part – to make it seem normal and ‘down-to-earth’. That’s how I also translate those aspects.

In your designs, we see a lot of collage, and also humour. Where do you pick and mix from, and what references are hiding in your design?

The process of picking those fabrics was a bit hard. On the one hand, I want to showcase how we can re-appreciate certain fabrics, and on the other hand, there is this conceptual translation of the Netherlands and my personal struggle. Every look tells a bit of a different narrative, which is essentially my life story assembled in one collection. There are also these references, like a patriotic Holland vest, as I just feel so disconnected from the whole idea of loving your country so much. It doesn’t exist for me. Why there is so much fuss about nationality, and I don’t even feel like I have one? I also wanted to bring this sarcastic vibe. My whole collection looks a bit ironic, and I think when exploring these serious topics, you need to make it a bit fun, otherwise, people won’t listen. My goal is to find a perfect recipe when I get people’s attention, and then we can talk about it. Everyone is tired of statements and the whole ‘bringing awareness’, and they kind of always reach the same people anyway. And then we only get more depressed, as there is no significant systematic change.

Can you tell me about the title? The Rebound Parley…

The title of my collection is linguistically playing on The Berlin Conference of 1884 I mentioned earlier. The literal translation of ‘rebound’ is ‘to bounce back after hitting something hard’. And ‘to recover in value, amount, or strength after a decrease or decline’. A ‘parley’ is described as ‘a conference between opposing sides in a dispute, especially a discussion that is intended to end an argument or about the terms for an armistice’. This summarises the whole spirit behind my work quite well.

Along with the title, several pieces speak to this precise narrative — and careful selection of words through material choices and so forth…

Yes, for example, there are several items in the collection that have these overloads of snap buttons. It’s both a conceptual translation of modern Black identity, which is never definitive, as well as offering the wearer the creative ability to adjust my vision of design and make it their own. One look is a pink dress made from four kids’ jackets moulded into one. The jackets are totally non-recyclable, it’s all microplastics. The heavy shapes seen in the dress are a translation of the clashing of borders and the Black struggle in general.

Art, and thus forth fashion, is innately linked to cultural and political issues. It’s impossible to solve these big issues on your own, but you can open a conversation — which is a huge emotional feat in itself.

It’s so great that Black Lives Matter happened, and that there is more awareness of inclusivity. After talking to so many people though, I feel like there is still a taboo around expressing conflict in identity because of having a mixed cultural background. It often feels like you have to choose between the two parents, and it’s so painful to see people struggle with it. And there are only going to be more mixed-race people in the world, so we need to talk about it. This is the main pillar of my work. It’s a never-ending story, you’re just trying to find who you are your whole life.

In such a multidimensional research process, what’s the biggest thing you’ve learnt?

For me, it was breaking free, actually. Throughout my life I’ve been code-switching my way around everything, constantly adjusting my behaviour. Just being very performative in the way you interact with people in different environments. I go to a Black barber, and the way I behave and talk there is totally different from how I am with my white teachers at school. I’ve also had this feeling I need to comfort and please people, so letting go of that part of me more has been very liberating. All thanks to the literature I’ve read.

Any favourite writers or pieces that you’ve come across?

‘White Innocence’ by Gloria Wekker was the biggest initiator for me to keep reading. There was also ‘The Black Experience in Design’, it’s about people of colour in arts and it really opened my mind up.

Being not alone and having a sense of recognizing yourself in someone else is so important. Which piece of your collection would you say is the most symbolic of your journey as a Black man growing up in a predominantly white industry?

I think the statue look that we talked about is a very powerful translation, a symbol to the point. I’m still most proud of the Ajax dress, it feels like a full-circle moment for me. Growing up and blindly loving Ajax as a teen, and then growing up to talk about it on a way deeper level. I think it’s an artefact of what I’ve been through as a person up to now.

FASHIONCLASH is set to be an exquisite showcase. What excites you about being a part of this year’s curation?

I really appreciate that I can tell my story to new audiences. After graduating, I already had the opportunity to do two shows and an exhibition. Now, I get to build a full installation around my graduation collection. I’m really excited to use new tools to express my narrative.

What do you hope your presence will share with the FASHIONCLASH audience?

I hope that there will be an interaction – I hope they take something home. You never really know what it is, of course. During my show at Lichting, in the background of my music, you could hear voices humming through the space, with very existential and intimate sayings, from the interviews I did earlier. I’m always trying to trigger and shock, to pinch people a little bit. Otherwise, it’s dull and will be forgotten.

Who else within the curation are you excited to see?

Of course, there is Pablo who is a great friend of mine. He’s also going to build an installation. I also get to meet my former teachers from Schepers Bosman there as well. Half a year ago, they told me, ‘enough with the conceptual research and the whole spiritual journey. You need to start sewing, otherwise, you’ll end up with nothing to show!’ And now, we’re at the same festival.

FASHIONCLASH – New Fashion Narratives #1

Friday 25 November | 18:30 – 22:00

Saturday 26 November | 12:00 – 17:00

Sunday 27 November | 12:00 – 17:00

WATCH ONLINE – Sunday 27 November | 17:30 – 17:50

Check out more here.

Notifications