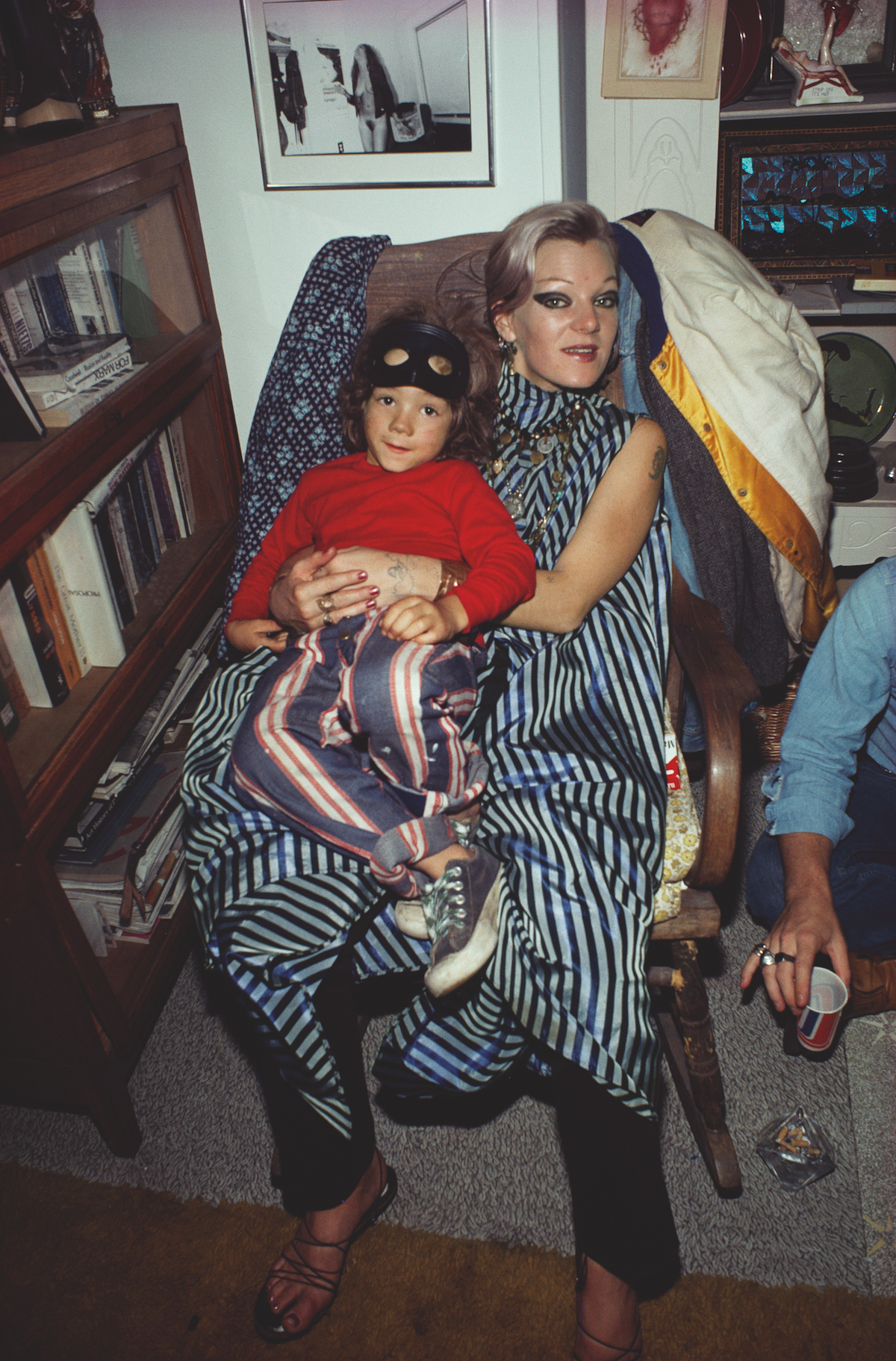

Nan Goldin, Nan on Brian’s lap, Nan’s birthday, NYC, 1981 © Nan Goldin

As many of you may know by now, Nan Goldin showed an exhibition of a lifetime at the Stedelijk last year. Over the weekend, this audio visual symphony came to a close. So in case you missed it – or just love Goldin – here is AT LARGE with Nan Goldin <3

May it be trust, an unbreakable bond, or the sacred connection between an artist and their muse. This is what opens a portal to a photograph—an immortalised moment, generously shared with the viewer. Fervent, unvarnished, stripped of any artifice is the ‘sacredness’ we reference laying the foundation for NAN GOLDIN’s approach. Today, Goldin’s monumental works are housed in the collections of the most significant art giants across the globe: from NEW YORK’s MOMA to LONDON’s TATE and PARIS’ CENTRE POMPIDOU, to name a few. Along with her victorious activism efforts (think taking down the Big Pharma company that facilitated the opioid crisis), Goldin is a powerhouse. This autumn, the artist returns to STEDELIJK MUSEUM for the third time with a multi-media retrospect, This Will Not End Well; a mesmerising exploration of the triumphs and tribulations that come with being alive.

“It’s a warning, but also a joke,” Goldin begins by explaining the title of the show unflinchingly. “Until you have embraced death, this will not end well for you.” With this sobering start to the conversation, Goldin provides a much-needed refresher; for it’s the acceptance of mortality that can allow us to tap into our humanity and take in the most—a key prerequisite to experiencing Goldin’s work. “Not many people find it funny, though” she laughs, unbothered. Joy, heartbreak, sex, friendships, and bereavement all gloriously exist in full intensity within Goldin’s reflection of the world. Within this spectrum, This Will Not End Well asserts Goldin as not only a photographer, but a filmmaker, as it encapsulates six different rooms of slideshows with archival stills, footage, and interview recordings, each diving into different yet interconnected facets of the human condition.

Nan Goldin, Jimmy Paulette and Tabboo! in the bathroom, NYC, 1991 © Nan Goldin

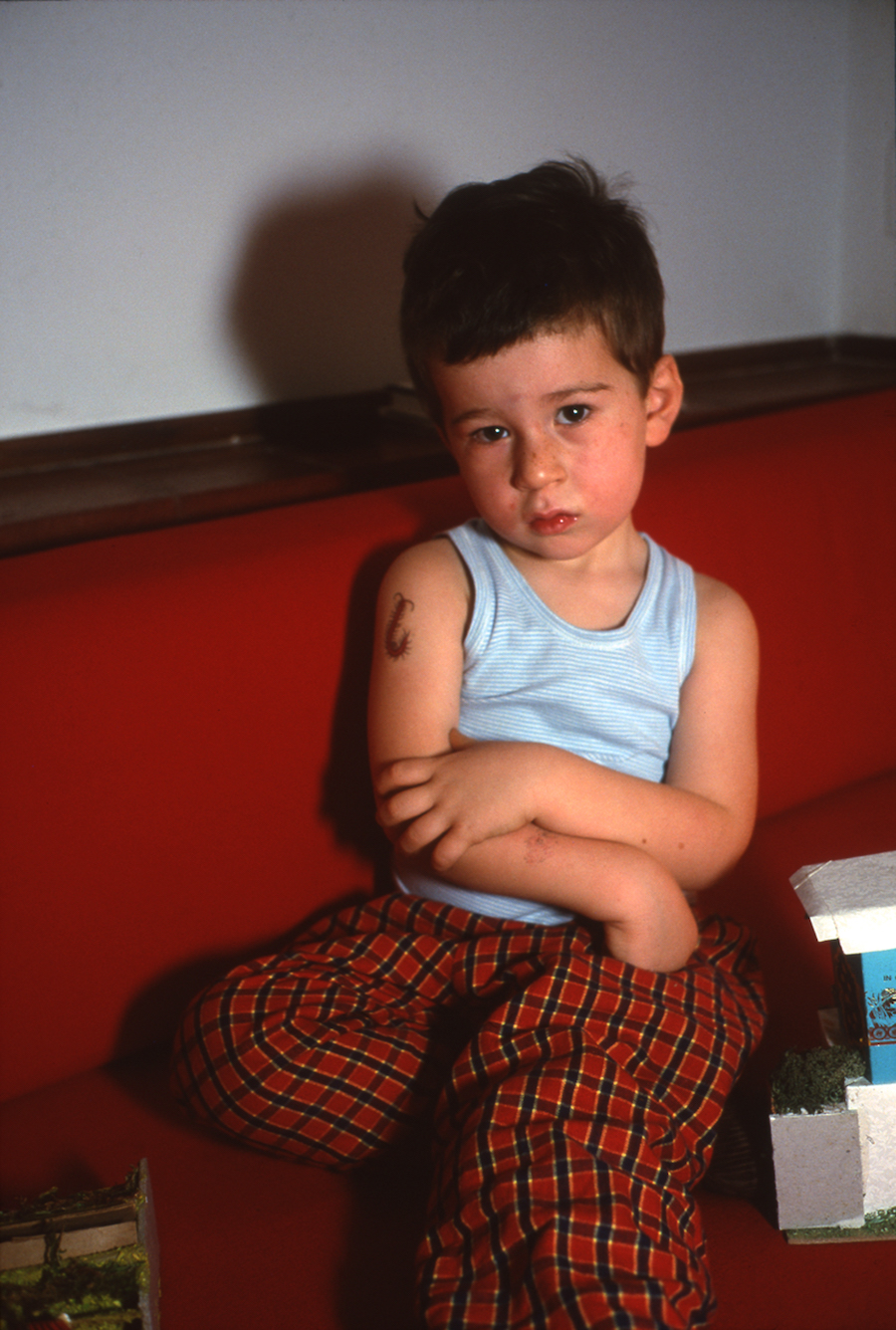

Nan Goldin, Max with a gun, Provincetown, MA, 1976 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Heart-shaped bruise, New York City, 1980 © Nan Goldin

Zooming out on her life and practice, Nan Goldin’s relationship with visual arts has been that of necessity. Her first camera gave her a voice—quite literally. Growing up in a WASHINGTON suburb in the 50s, Goldin was confronted with the dysfunctional dynamics that dominated her surroundings from a very young age. “I was eleven when my sister Barbara committed suicide,” she recounts in the introduction of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, her most renowned book and slideshow dedicated to Barbara. “I was very close to my sister and aware of some of the forces that led her to choose suicide. It was an act of immense will.” BARBARA GOLDIN dared to challenge her over-controlling and dismissive environment, in which any woman straying away from the submissive ‘norm’ was demonised. Following the tremendous loss, Nan Goldin stopped speaking for several years until she ran away from home at the tender age of fourteen. She enrolled in an alternative liberal school, which is where she first found her tribe and belonging—as well as her first Polaroid camera.

Photography became Goldin’s way of processing, questioning, and documenting the world around her. Apart from making life-long friendships (such as fellow photographer DAVID ARMSTRONG), it was also a fundamental time during which she first fell in love with cinema. Shortly after graduating, she and Armstrong moved to BOSTON, where Goldin began recording alongside the transgender community she lived with. It’s these works that solidify her slideshow The Other Side, which eventually combines her works from NEW YORK, BERLIN, PARIS, AND BANGKOK in its latest version shown at Stedelijk Museum. Named after a bar they frequented, the series celebrates the “gender euphoria” experienced by those who refused to live within the confines of the gender binary. “My dream since I was a kid was of a world with completely fluid gender and sexuality, which has come true as manifested by all those living publicly as gender non-conforming”, she writes in the exhibition notes.

Setting her apart from her contemporaries, such as SALLY MANN and DIANE ARBUS, Goldin has always been an active player in any scene she portrays, a vital element in the microcosm of her community. There is no voyeurism in her work, no disappearing behind the camera—it was Goldin’s world as much as it was her subjects’. “The trust that my friends gave me to photograph them is key”, she reiterates in her contemplation. Within this, the intimacy that runs through Goldin’s photographs is conceived and nourished through her relationships, not mere observations. “Intimacy is something that grows in relationships and has nothing to do with the public eye,” Goldin assures that friendships become the real art, and it’s Goldin’s loving eye—before her lens—that makes her photographs so strikingly spirited.

Nan Goldin, C putting on her make-up at Second Tip, Bangkok, 1992 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Amanda at the sauna, Hotel Savoy, Berlin, 1993 © Nan Goldin

Setting her apart from her contemporaries, such as SALLY MANN and DIANE ARBUS, Goldin has always been an active player in any scene she portrays, a vital element in the microcosm of her community. There is no voyeurism in her work, no disappearing behind the camera—it was Goldin’s world as much as it was her subjects’. “The trust that my friends gave me to photograph them is key”, she reiterates in her contemplation. Within this, the intimacy that runs through Goldin’s photographs is conceived and nourished through her relationships, not mere observations. “Intimacy is something that grows in relationships and has nothing to do with the public eye,” Goldin assures that friendships become the real art, and it’s Goldin’s loving eye—before her lens—that makes her photographs so strikingly spirited.

Moving to New York, one of her current home bases, Goldin dived deeper into her craft, extending her chosen family. “Nan’s passions—their depth and violence and complexity and contradictions—drew her to those who were ruled likewise”, writes LUCY SANTE, Goldin’s friend, when describing the artist’s existence during that time. “When their powerful energies confronted hers, the resulting combustion created something more than a portrait.” Drag queens, drug users, sex workers, kisses on lips, syringes piercing the skin, emotional entanglements and their demise, caresses and bruises—all make up an emotional whirlwind of human experiences, often overlooked or tamed, reflecting the turbulence that often accompanies true passion. With Goldin’s work being heavily politicised and recontextualised, I felt a strong sense of aversion to answering mundane questions and clarifying her work to others from her side. “When I make my work, it comes from the personal and from collaborations with people who are close to me,” she states with a stern protectiveness. “But when I show it, it intends to fight the stigma against mental health, suicide, AIDS, drug use.” Goldin remains concise with her explanation.

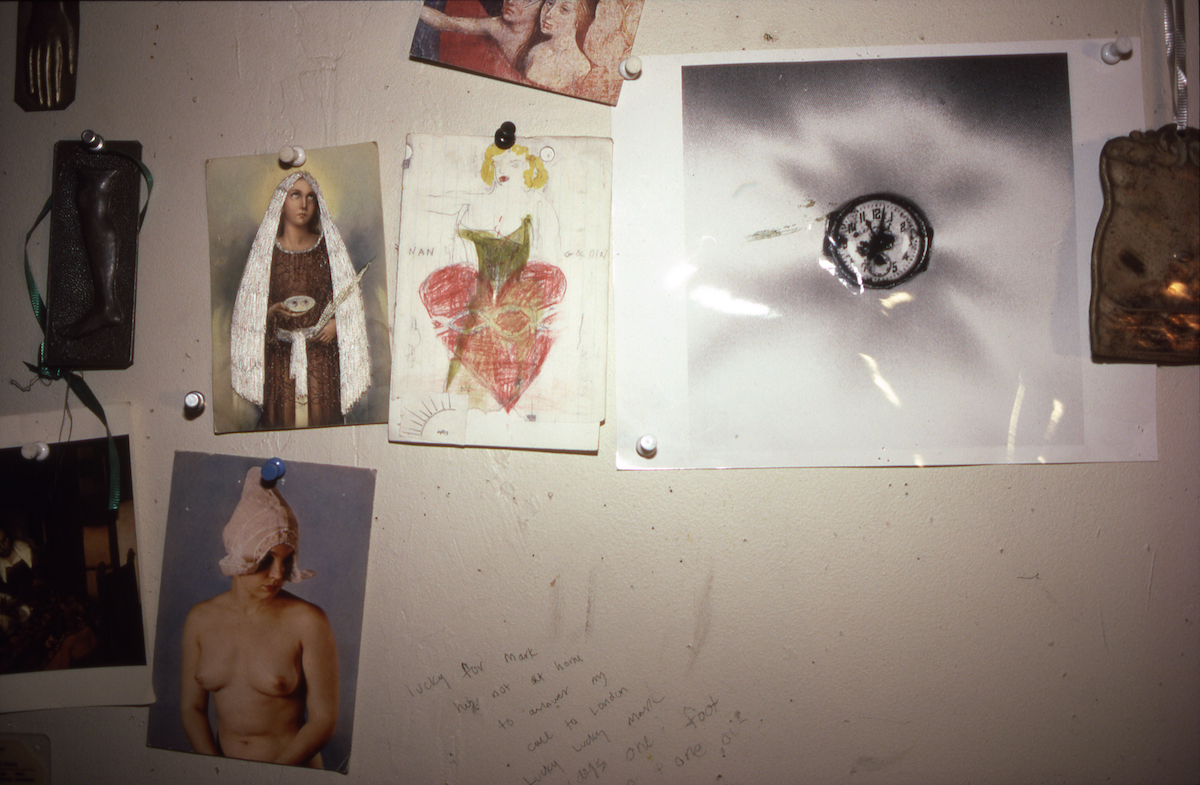

Nan Goldin, Writing on my wall, Bowery, NYC, 1988 © Nan Goldin

With this, analysing Goldin’s work from a technical perspective or a premeditated political stance feels intrusive, almost perverse. Her and her friends’ stories and bodies should have space to exist freely, without carrying the weight of controversy, scandal, or ideological connotations imposed by outsiders. Goldin created for herself and the people she loved—as the earliest slideshows of the seminal The Ballad of Sexual Dependency frolicked on the walls of clubs, underground cinemas and birthday parties exclusively for her friends, way before finding their way to museums. Her photographs blossom when looked at emotionally, and gain radicality when Goldin chooses to put them in a specific context herself. “In ’89, I curated the first show about AIDS in New York, called Witnesses,” Goldin recalls when I asked when she first realised the gravity of the impact she was making. “The government tried to censor it, and I found a lot of power in fighting back. All my life I had felt like I succeeded. I didn’t know ‘the bar’— I didn’t feel that drive to compete,” she says with a modesty disproportionate to her artistic standing.

Of course, photography will inevitably have a complicated relationship with truth. Still, her truth is different to those who existed at said ‘bar’; her truth can’t be replicated through a red lipstick decisively smudged by a make-up artist or a messy room carefully constructed by a set designer. “My intent is for people to feel what’s on the screen in their bodies.” Goldin reflects. And she achieves that—her truth is visceral, it lingers, it follows the viewer and grows within them.

Nan Goldin, French Chris on the convertible, New York City, 1979 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Greer modelling jewellery, NYC, 1985 © Nan Goldin

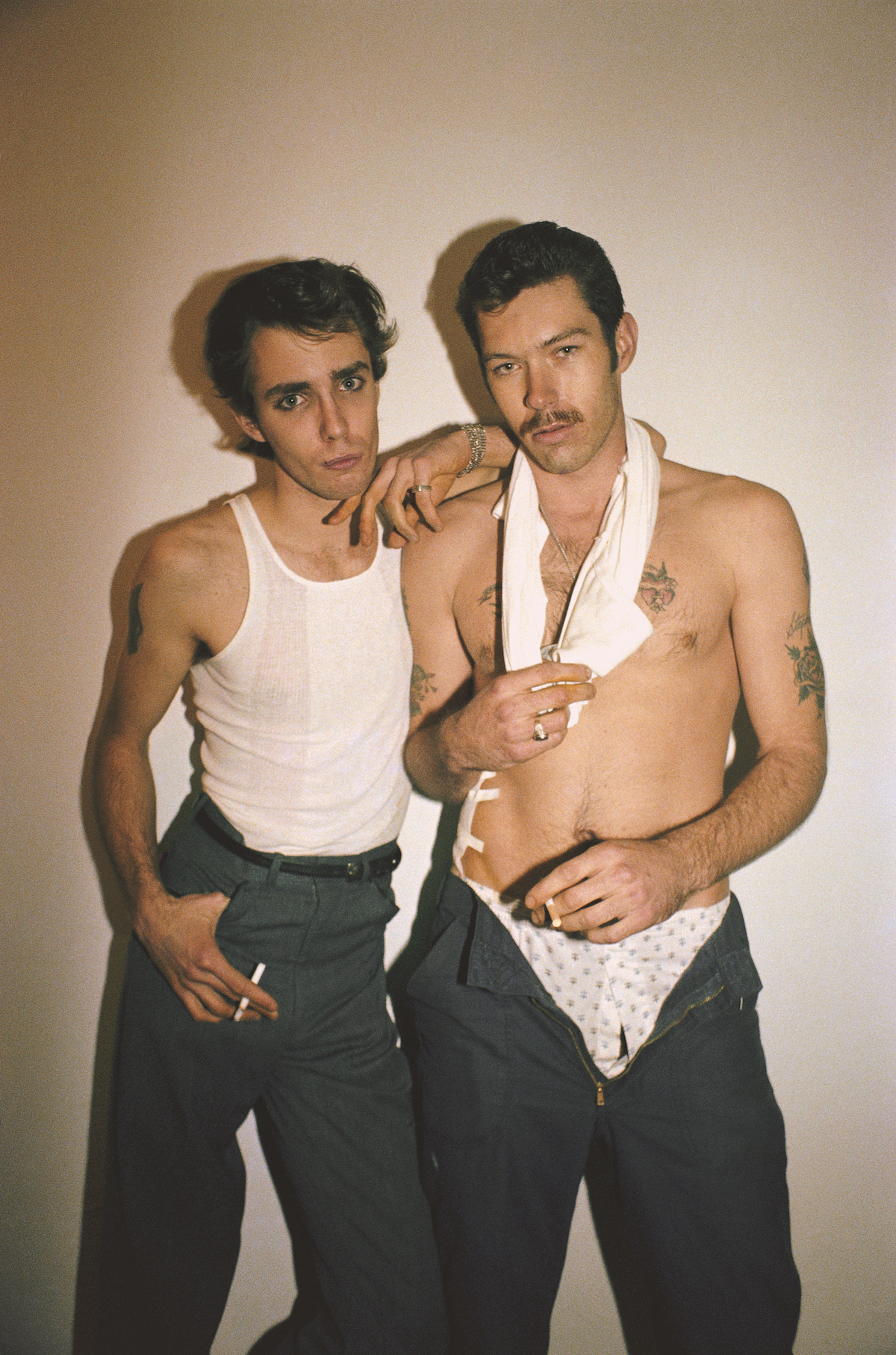

Nan Goldin, Bruno with the tattoo, Naples, 1995 © Nan Goldin

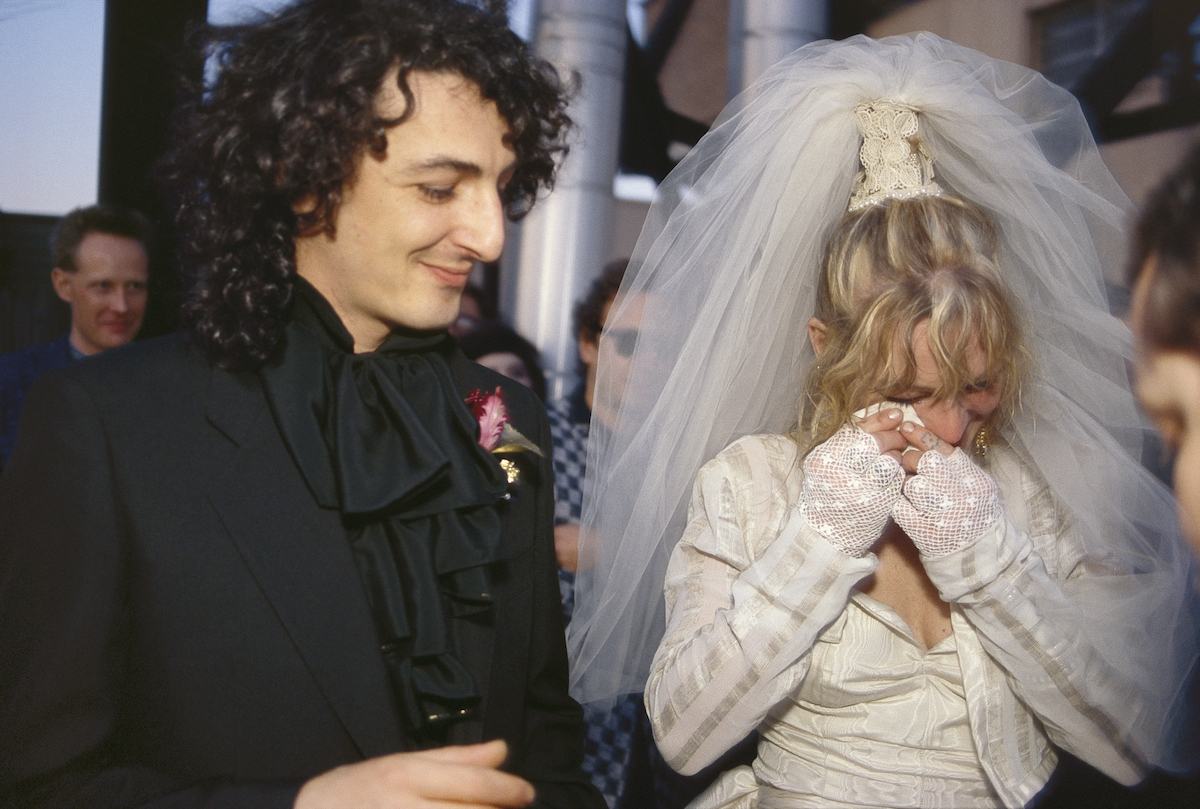

Today, This Will Not End Well envelopes that truth with an unprecedented magnetism. The hypnotic show consists of six separate bodies of work—The Ballad of Sexual Dependency; The Other Side; Memory Lost; Fire Leap; Sisters, Saints, and Sibyls—all representing the latest rendition of Goldin’s canon. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is a vertiginous dance between Goldin and her people, most of whom she had lost to the AIDS epidemic. 700 hundred images in a 45-minute slideshow, The Ballad is both a chronicle and a relic—from her friend COOKIE’s wedding to her deathbed, from her lover BRIAN’s embrace to the bruises inflicted by his fists.

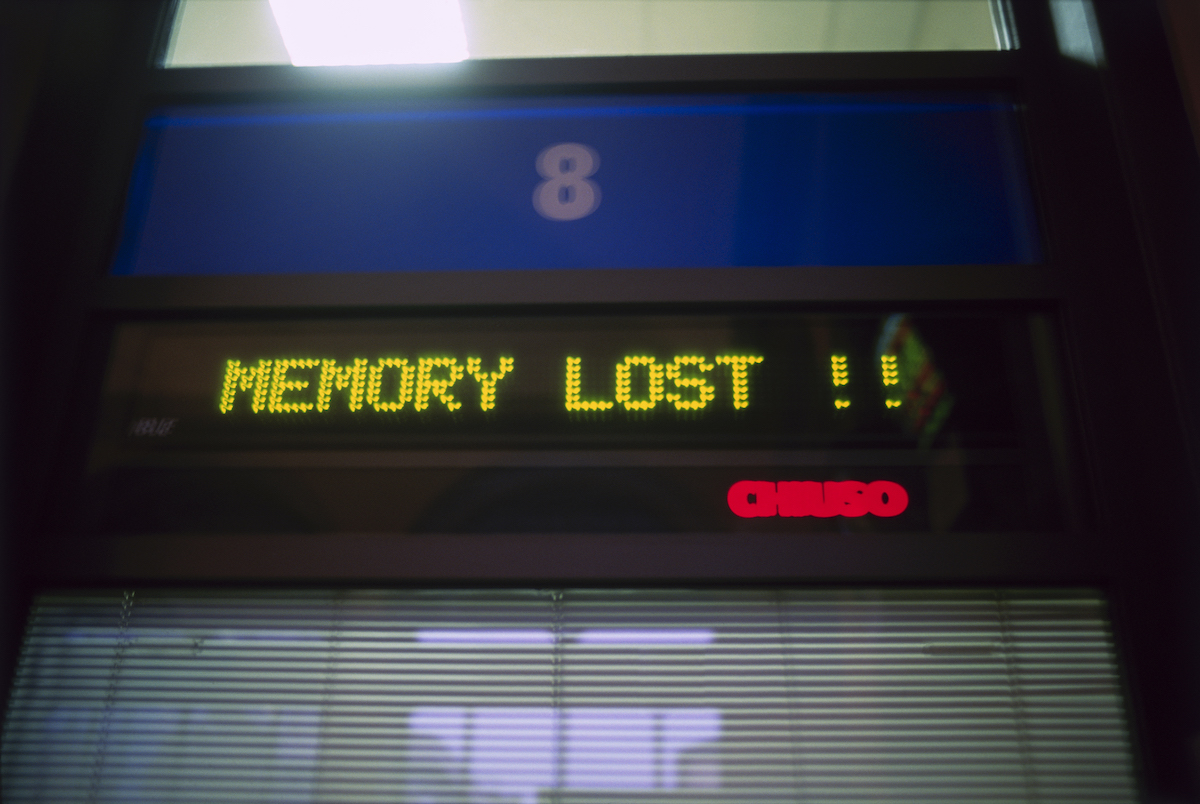

Next, we arrive at the claustrophobic entrance to Memory Lost, a furthering spiral into the dark side of addiction. “Nan, are you there? Are you sleeping?”, a voice from a telephone answering machine rolls hauntingly over a procession of blurred photographs. Stemmed from Goldin’s own experience with addiction, Memory Lost is a reconstruction of immense pain and a reminder that what one may seek in addiction is human. It is also impossible to talk about this piece—or Goldin’s career as a whole— without recognising her activism. From her early affiliation with grassroots activist groups in response to AIDS, to founding her group, P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), Goldin is uncompromising in her demands for what is right. The recent Oscar-nominated documentary All The Beauty And The Bloodshed dedicated to P.A.I.N., shows the takedown of the Sackler Family—responsible for the opioid crisis due to their over-prescribed, highly addictive painkiller OxyContin—as a gruelling process. The company’s immense profits fueled their ‘philanthropy’ in art institutions like MoMA, Guggenheim, and Louvre, all bearing the “Sackler” name on their walls. “We made a big noise”, says Goldin, proudly. “We got rid of their name at every university and museum in the world. Now, we are focusing on keeping drug users alive.” Sadly, but unsurprisingly, this had taken a toll on Goldin’s artistic career: “There have been a couple of institutions who wouldn’t take my work because of the people they depended on,” she shares. Gladly, and respectfully, Goldin does not give a shit. “I don’t know who I’m going to take down next,” she chuckles with youthful mischief in her voice.

Nan Goldin, My bedroom at The Lodge, Belmont, MA, 1988 © Nan Goldin

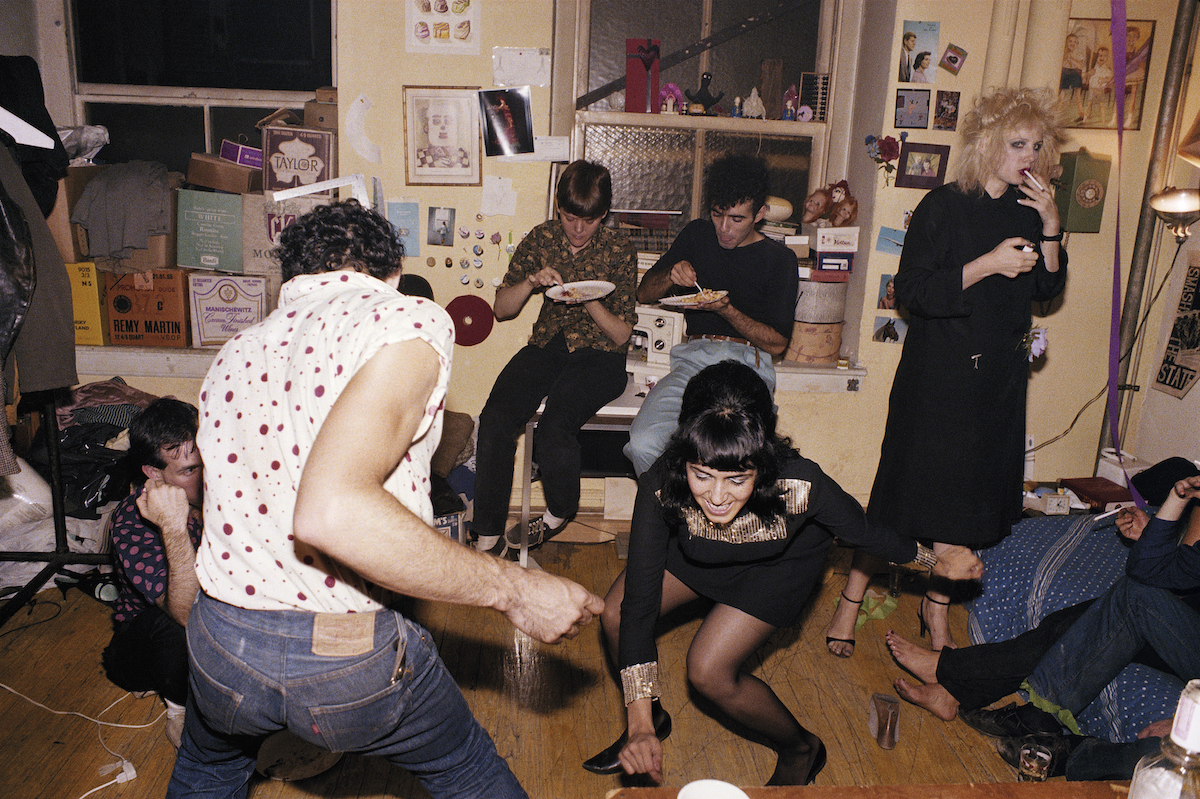

Nan Goldin, Twisting at my birthday party, NYC, 1980 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Cookie and Vittorio’s wedding, NYC, 1986 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Picnic on the Esplanade, Boston, 1973 © Nan Goldin

Moving further through the exhibition, you see Sisters, Saints, and Sibyls, a cinematic triptych and a heart-wrenching eulogy. “People are meant to go up this structure that mimics a New York fire escape, and be stuck on a balcony,” Goldin explains the architectural intention that foreshadows the emotional charge in the room. Conceived in the church of LA SALPÊTRIÈRE—the former mental hospital where Barbara had been institutionalised,—the piece explores the stories of “women who are trapped, literally and figuratively”. Chilling sounds of a medieval choir and matter-of-fact voiceovers accompany Goldin as she traces back her family photographs, returns to the train tracks where Barbara had committed suicide and tells a story of her survival. As a backdrop, Goldin interweaves the Christian legend of SAINT BARBARA, a beautiful daughter of a pagan, who locked her away to protect her from the gazes of men. In response, she challenged the male-dominated system and faced repercussions for her courageous actions.

Nan Goldin, Gina at Bruce’s dinner party, NYC, 1991 © Nan Goldin

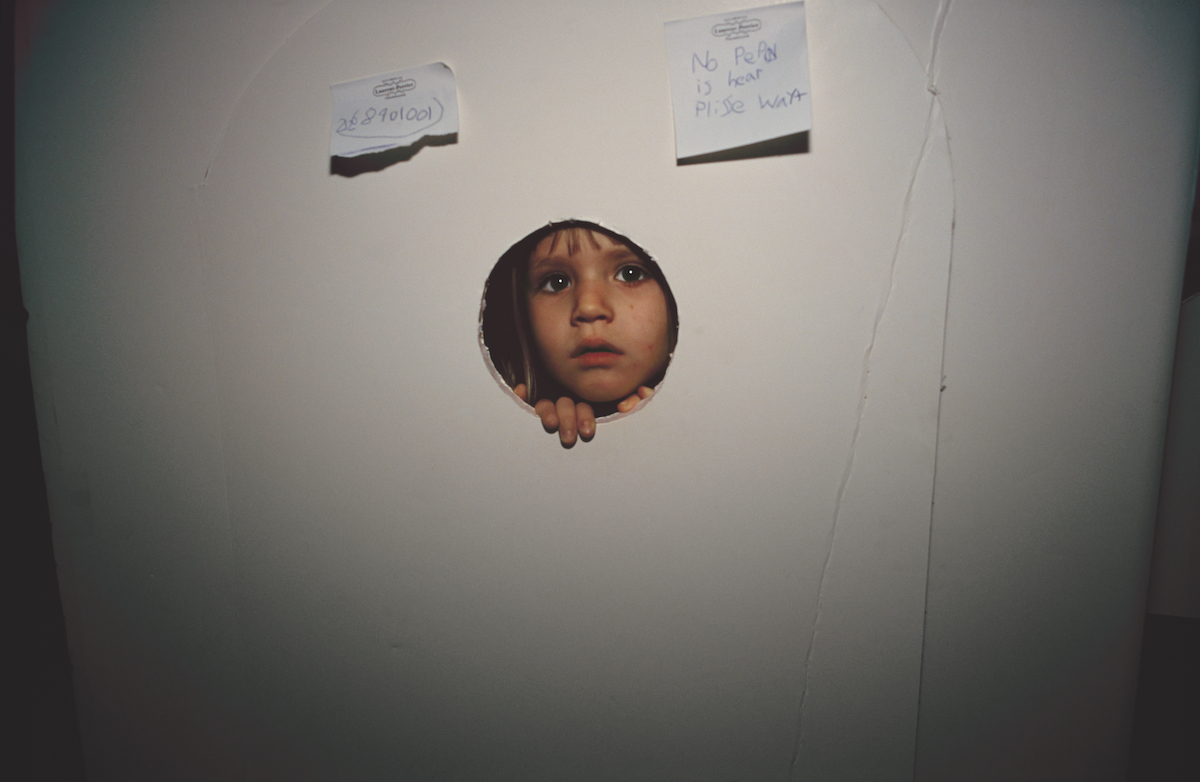

Nan Goldin, Nikki in a box © Nan Goldin

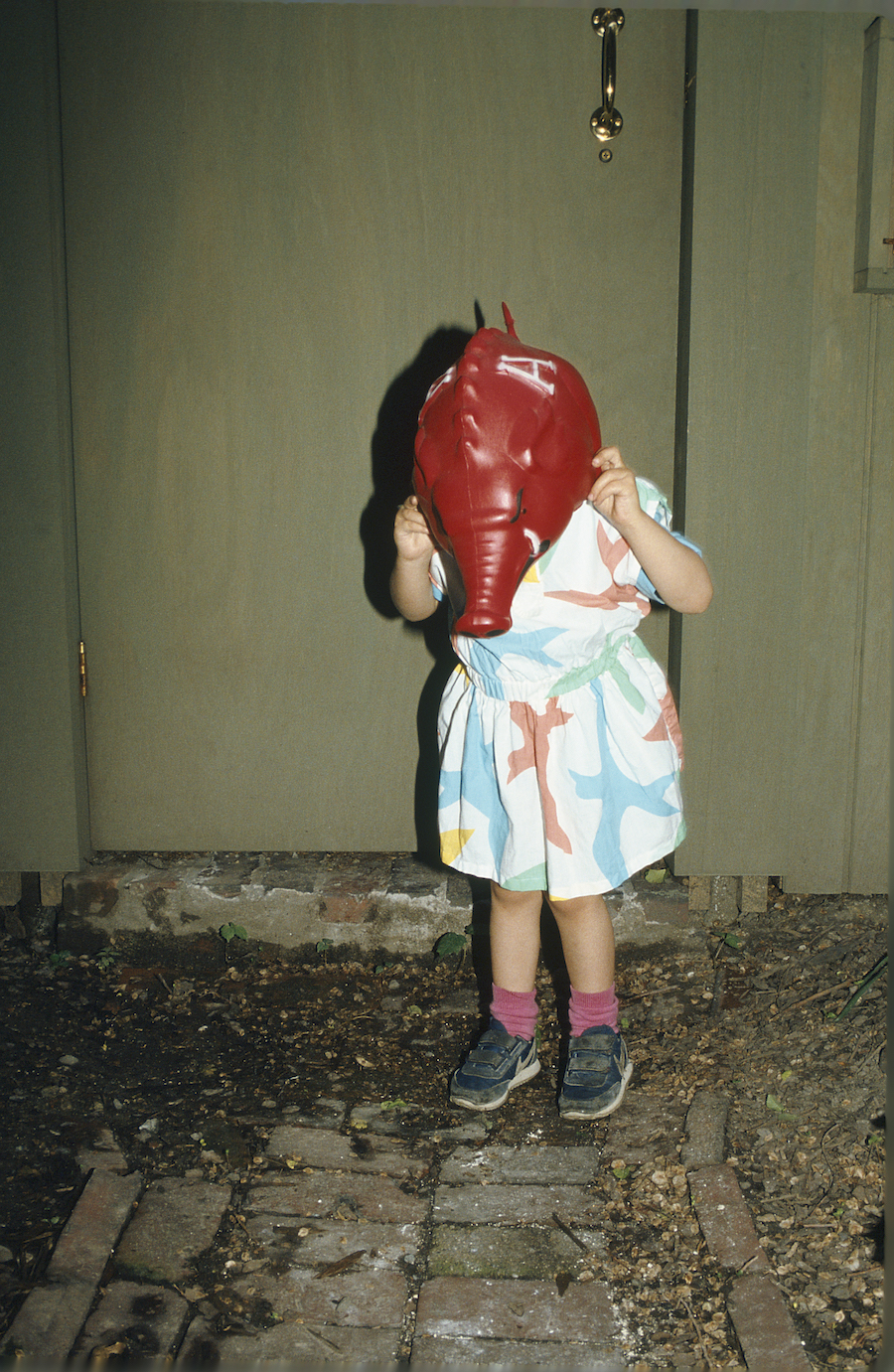

Nan Goldin, Elephant mask, Boston, 1985 © Nan Goldin

The exhibition also features Fire Leap, one of Goldin’s recent works dedicated to the freedom of being a child. “When children arrive, they know everything, and life teaches them to forget,” she writes. Snotty, half-dressed, frustrated, naughty, loving—Goldin tenderly captures her friends’ children, taking a dip into their world of unrestrained imagination. “I always wanted to make films, since I was a kid,” she now recalls, in a beautiful full circle moment. I would like to think Goldin feels closer to her child-like self, too. “I’d like to think of my slideshows as films made of stills,” she continues. Indeed, her slideshows certainly do not lack a storyline, character development, and dynamism. They become their living and breathing organisms, a constant work in progress. “My slideshows are the most proud work I’ve ever done,” she concludes,—and rightfully so.

“I’m very grateful that younger generations respond to my work. It is a gift to me.” Goldin says with humility and a certain dreaminess in her voice as we approach the end of our conversation. “But you have to get off social media!” she switches to an almost motherly tone “There is just so much more for you…” Like a red-haired spirit bestowing her wisdom upon my innocence, Goldin swiftly vanishes to smoke a cigarette on the Stedelijk’s balcony—and I am left with a strange warmth dispersing over my body. However unachievable it may seem, her simple advice is a reminder of humanity and empathy that can only be fostered and lived eye-to-eye, flesh-to-flesh.

Nan Goldin, Ivy in gloves at Myrtle St, Boston, 1972 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Porta Nuova, Turin, Italy, 2000 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Suzanne on her bed, New York City, 1983 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Mark and Mark, Boston, 1978 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Kim in rhinestones, Paris, 1991 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Self-portrait in blue bathroom, London, 1980 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Stills from Sisters, Saints and Sibyls, 2004-2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Stills from Sisters, Saints and Sibyls, 2004-2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Stills from Sisters, Saints and Sibyls, 2004-2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Stills from Sisters, Saints and Sibyls, 2004-2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Stills from Sisters, Saints and Sibyls, 2004-2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Cookie with Max at my birthday party, Provincetown, MA, 1976 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Brian and Nan in Kimono, 1983 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Misty and Jimmy Paulette in a taxi, NYC, 1991 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Amanda on my Fortuny, Berlin, 1993 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, The Hug, New York City, 1980 © Nan Goldin

Words by Evita Shrestha

Thank you Stedelijk Museum