THE HARD CANDY ISSUE – OUT NOW

“You ask me a question, and I go into a hundred different directions in my head,” laughs Lois Cohen, the visionary and award-winning Amsterdam-based photographer whose work shatters expectations. Her apologies for the digressions render themselves gratuitous, as I truly believe that going off on tangents is the best part of any interview. These ‘hundreds of different directions’ are testament to Cohen’s work and the mind behind it—immeasurable, erratic, labyrinthine. Inherently allergic to mediocrity, the artist is devoted to challenging norms and forging her own uncompromising way of decoding reality.

Cohen’s first creative memories run deep into her early childhood. “I practically barricaded myself in my room to spend endless hours drawing, shutting out the world beyond,’ she reminisces. But it soon turned out that the idealistic nature of her character wasn’t that compatible with the medium: “It was also frustrating,” she shares. “I’d get very perfectionistic and brush a hole in the paper, so I’d throw the whole piece away.” In parallel, Cohen’s passion for theatre began to grow—a practice in which she constructed her own universe, without the forced permanency of having it etched on paper: “I was transforming myself into different characters in elaborate costumes and staging performances for my imaginary audience.’ With dolls as her ‘co-stars’ in grandiose productions with ‘completely unhinged storylines’, Cohen was ready to take over the world.

Her passions quickly fell into place when Cohen started to capture her self-produced spectacles through her father’s point-and-shoot: “I started with self-portraiture and eventually began abusing friends and family, dressing them up and photographing them in weird scenarios,” she jokes. “Essentially, what I do is a way to keep extending my childhood.” For the viewer, too, Cohen’s work opens up a portal to youthful freedom we often repress. As her imagination races across her photographs, we are encouraged to keep up—the themes may be more grown-up, but the principles of play must be abided by. There is no such thing as too fantastical here.

Moving into adolescence, Cohen’s formative years were shaped at an arts high school ‘run by old hippies’ in the heart of Amsterdam. “It was a creative safe haven for all the eccentric kids who got bullied for being the weirdos of the class in elementary school,” she remembers of her first experiences of being surrounded by like-minded individuals. “Being a freak was the norm,” she adds, recalling smoking cigarettes in class and buying psychedelics from teachers. This place of lawlessness provided Cohen with a sense of belonging and resonance with other ‘freaks’: “I was surrounded by squatters, goths, emos, punks, hippies and ravers.” Not identifying with any of them fully yet constantly floating at their intersections, Cohen harboured a perfect observer/insider balance which has allowed her to portray communities and individuals with an intimacy that always feels authentic.

As with most things in life, the dichotomy of the good and the ugly is strongly embedded in Cohen’s experiences: “While the environment I grew up in was undeniably beautiful, it also contained a grimy side. I remember three dreamy girls from high school with angelic faces, long greasy hair and flowy dresses,” she reminisces. “They delved deep into witchcraft and experimented extensively with psychedelics, seeking to connect with the supernatural. Sadly, they ended up in a mental hospital, and one of them never recovered.” This is just one of many examples Cohen tells of having witnessed those around her lose their way due to drugs and failed mental health care. “I’m a very forgetful person,” she says frankly. “A lot of my memories have holes in them, which I fill with delusion.” It’s these ‘blank spaces’ in the non-linearity of our perception of time that largely fuel Cohen’s ideas.

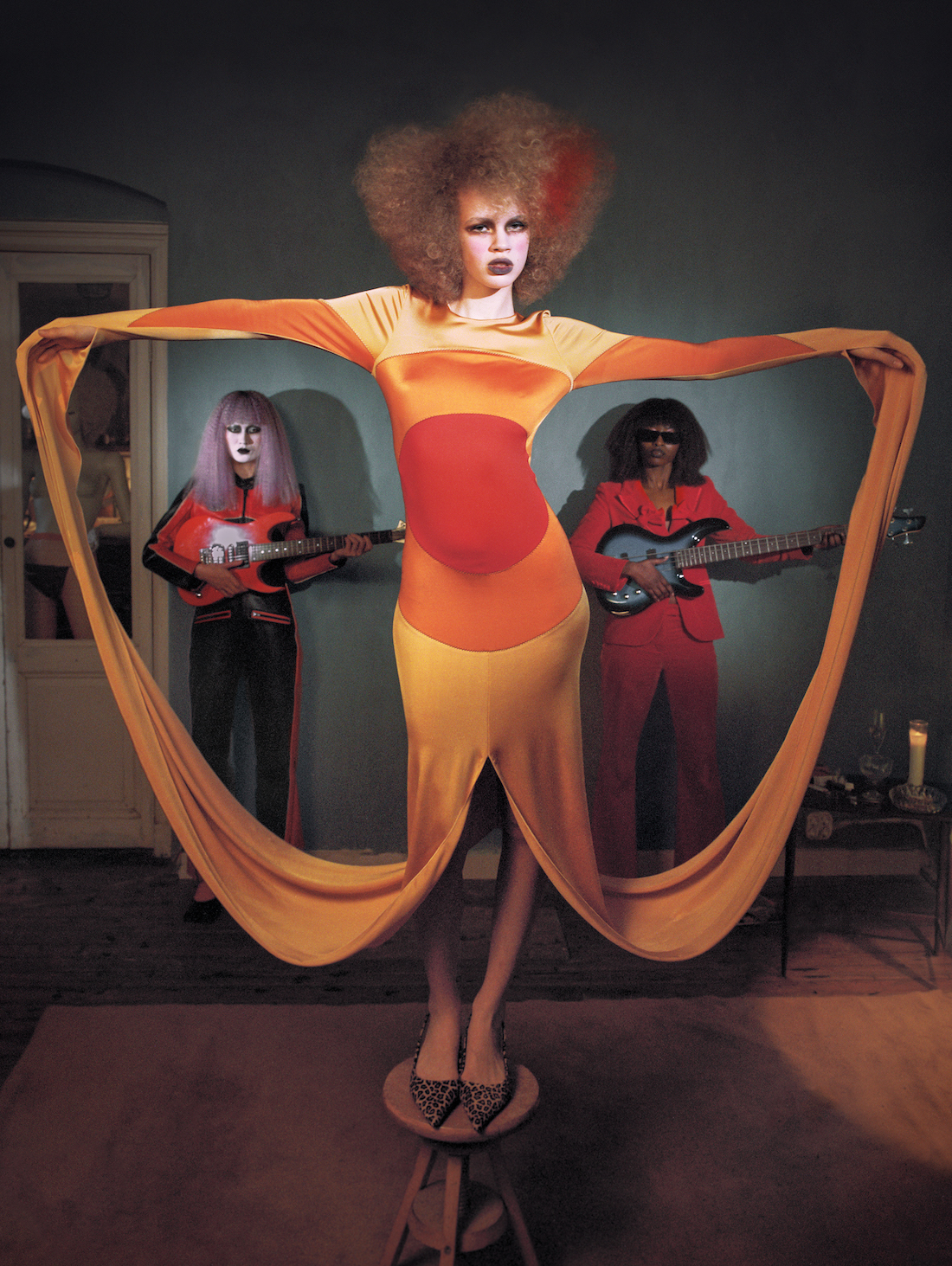

A significant source of inspiration for Cohen is ‘celebrating human beings’, primarily focusing on women. Describing herself as ‘a notorious people-watcher’, she has an incredible eye for anything that steps out of the average. “I favour eccentric individuals and countercultures that ignore social norms and isolate themselves from society, but am equally intrigued by those who care too much and try too hard to fit in, to the point of overdoing itt.” Suspending her work in the space of tensions and contradictions, Cohen’s irreverent approach “looks for beauty in what the masses consider ugly and corrupts what is thought to be beautiful or morally high standing”. Visually, Cohen gives her characters power, no matter what extreme they represent. By constructing stories around her muses or transforming them into completely fictional beings, Cohen continues the legacy of her younger self. In combination with intricate stagecraft and effortless storytelling, it feels as though her subjects observe our world from theirs, and not the other way around. Their lives extend beyond the frame, blurring the line between the actor and the onlooker.

In selected projects, these notions of subversion are seen throughout, no matter how diverse the core concepts are. ‘Metamorphosis’, a collaboration between Cohen and her friend Indiana Roma Voss, was intended to deconstruct male-coded and white-washed representations of women throughout history. The result is a rich and reference-packed iconography of modern womanhood. Resembling paintings, the ‘Metamorphosis’ portraits serve as an immortalisation of inclusivity and rebellion against artificially set boundaries of expression.

With ‘Gabber is Family’, this disruption of a familiar archetype continues. “The stereotypical media image of the Gabber community is aggressive bald-headed maniacs addicted to speed and pills,” Cohen says, disapprovingly. “But there is also a really wholesome side to Gabber that is so overlooked.” Originating from Rotterdam’s Nineties youth culture, Gabber’s radical aesthetic remains an oversimplified reference in fashion and cinema. For Cohen, though, it was important to connect to a softer side of a hardcore scene: “The sense of unity is very strong, which led me to the idea of portraying a big Gabber family across different generations. Even including Gabber baby and Gabber grandad.” While still being staged and partly modelled by individuals outside of the community (turns out, finding a real Gabber baby on short notice is no easy endeavour), the documentary approach is still felt. “We made sure that most of the cast consists of real Gabbers, and some of the subjects are actually related,” Cohen confirms. “We also pulled a lot of clothing from their own wardrobes. I wanted it to be real Gabber—no fashion shit.”

It’s interesting to consider Cohen’s progression toward nonfiction in the context of her inspirations. Her main influences—like Diane Arbus, William Eggleston and Ed van der Elsken—all base their practice around street or documentary photography. But when it comes to cinema, she has ‘a weakness for fiction’. Listing her favourites, she mentions the old Tim Burtons, like ‘Beetlejuice’ and ‘Big Fish’, for their elaborate sets; ‘Bladerunner’ for the neon-lit atmospheric scenes; and ‘Phantom of the Paradise’ for its over-the-top absurdity. An honourable mention also goes to cult classics and trash reality TV with ‘a high level of camp and bimbo culture’, such as ‘The Stepford Wives’, ‘Real Housewives of Beverly Hills’ and ‘The Simple Life’. Combining a melting pot of bold sensibilities and unconventional narratives, her work represents a witty play on the ironies of the everyday.

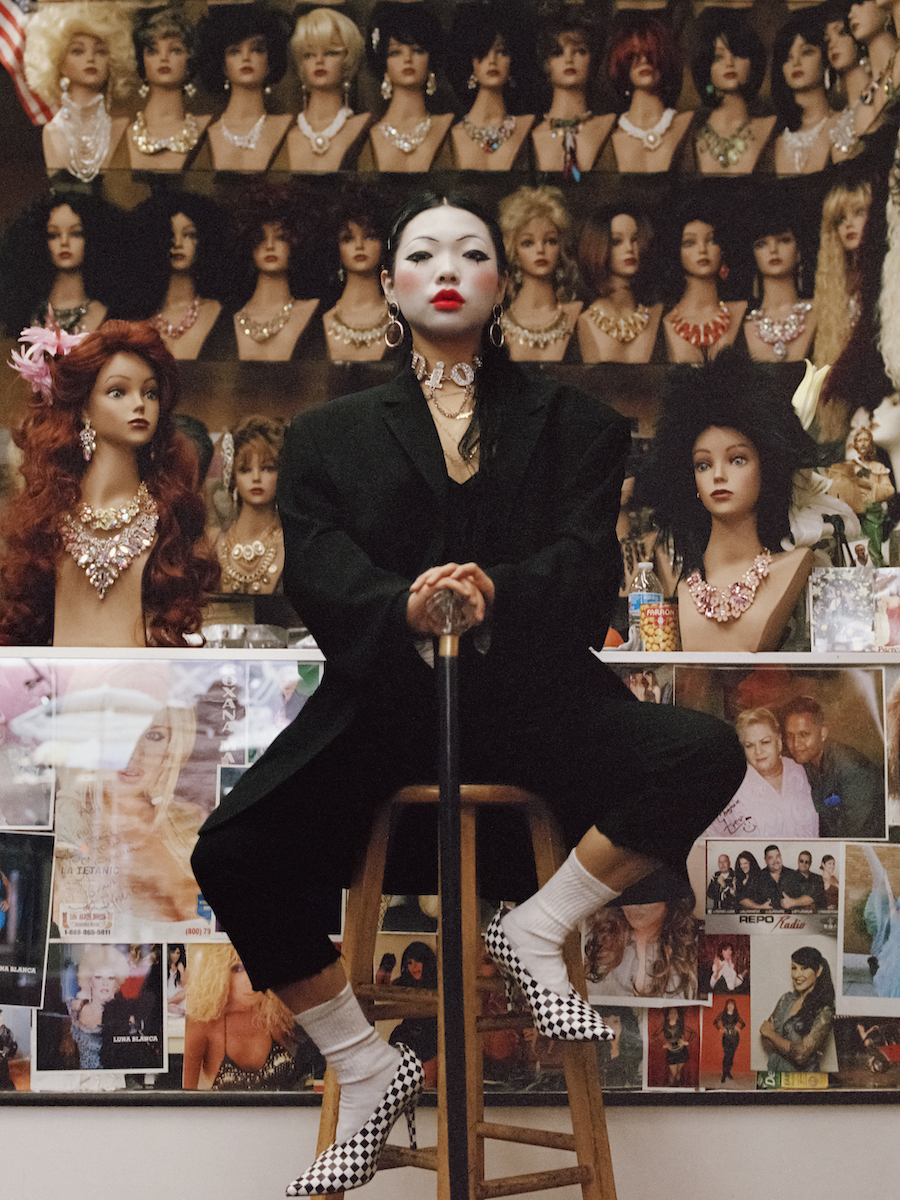

Cohen’s most recent ‘Beings (part 1)’ series takes that even further, contending with collective hysteria around the swift emergence of AI and the implications it may have. “I invited a group of friends to hang out with my collection of mannequins,” she recalls. “I’m used to telling my models exactly how to look when I have a composition in mind, almost as if they are dolls. Since I was working with an actual mix this time, I would often get confused about who was real and who wasn’t.” Startled by this disorientation, Cohen immediately realised that this confusion “mirrors the state of our current existence in the age of AI.” As the project progressed, her questions of how humans interact with technology began to deepen. “Could genuine love exist between a human and a machine?” she ponders, and we can sense her mind dispersing into a myriad of different paths. Cohen’s affinity to dolls is no secret, but this series is not dedicated to mannequins; it’s about the interaction between the organic and artificial in “a world where both humans and nonhumans are released from the pressure to be hyper-productive machines.” A social commentary that yet again fuses the separation. “The moments of intense dissociation and alienation that occurred amongst the group were also telling,” she says. “It quickly became a dystopian experience.”

As unsettling as living in the ‘uncanny valley’ may be, Cohen is confident that photography is not under threat from AI: “There’s a lot of fear with AI. But I think it’s completely different from photography. The power of photography is that it captures reality, even if it’s altered or indistinguishable from an AI-generated product. People will always be drawn to that authenticity.” Still, Cohen senses a cultural transition that is reshaping how we interact with visual imagery: “If anything, photography could become a dying art because everything is turning to moving images.”

Luckily, Cohen’s art is not dying any time soon—just evolving. In a wide reflection upon her work, her shift to obscurity stands out clearly. “When I began photography, I wanted to create my versions of a utopia,” she muses. “And while my work is still dreamlike, I’m now drawn to more dystopian elements.” This transformation is manifested in dampened, pastel colours and a cryptic cinematic approach. “A shift in my overall mood has led me to delve into darker and more uncanny themes surrounding the human psyche, womanhood and our relationship with artificiality.” Drawing from her current favourite conceptual artists like Mike Kelley and Charles Ray, and painters like Francis Bacon and Aleksandra Waliszewska, her practice continues to grow layers of existentialism. “At first I aimed to empower; now I’m more interested in creating feelings of mild discomfort.”

As a translator of reality, Cohen is determined to keep uncovering veils of human experience in the most unrestricted way. With her sharp perceptiveness to the surroundings (she lists her inspirations as “everything from ancient religious scriptures to random TikTok videos”), Cohen’s vision is a much-needed change of perspective. “I believe to capture the chaos of the world today, I need to get lost in the circus and embrace the noise instead of filtering it out,” she concludes. “The good and the bad…”

Words by Evita Shrestha

Images courtesy of the artist

THE HARD CANDY ISSUE – OUT NOW