As always, we’re on the hunt for the most interesting upcoming names in the industry, and every year we’re lucky to discover some incredible gems at KABK. We’ve had the pleasure to get to know three of their graduates who must be on your radar – meet MATEVZ ČEBAŠEK, JULIE GOSLINGA, and DANS JIGERSONS. They’ll be showcasing their graduation collections June 27th until July 2nd. Make sure you don’t miss it!

Matevz is a passionate visual storyteller whose work explores the realms of memory, history, and personal identity. His graduation project is a photographic story of his grandmother’s dementia, using her fragmented recollections to weave a narrative that intertwines personal and collective histories. Through his lens, Matevz captures the essence of his family’s past, shedding light on how individual stories can reflect broader historical events. His work is a tribute to memory, family, and the landscapes (physical and metaphorical) that shape our lives.

Hey Matevz! Nice to meet you. Can you tell me about the story behind your graduation work?

My story is about my grandmother who has dementia. I started working with dementia in the second year of my studie. At that time I was working on a story about my grandfather. Then during that period also my grandmother’s dementia got worse, so it felt natural for me that I continue to work on that story. In the end, the project turned out to be more about memories and how we perceive the past, and comparing this subjectivity of memories to the subjectivity of written history. I’ve been exploring how collective history can also be told through very personal stories, and using dementia as an example of these fractured memories.

Is there any specific collective history you reflect on?

Yeah, I was really dependent on my grandmother’s stories, so basically I took the events that stayed in her head. The events that really traumatized her or really influenced her come back the most – so I start with the Second World War when she lost her father, during the German occupation in Slovenia. Another important part is in the 90s when her husband got sick, but she’s not really remembering that, so it’s more asking her about the period when they met, in the 70s. For the region she’s from, this was an important moment because it was very industrial, and a lot of young women from the villages went to work there (including herself). So that’s also a big parallel, because when I was going to these museums of the region, I actually saw her stories there, even though it was not about her. I think historically those are the most important stories. Other than that, it’s also personal recollections.

Aesthetically speaking, how have you translated this story to be conveyed in your graduation work?

I was not really looking for aesthetic references, it’s just a combination of all the things I saw through the years. The visual style that was developing in the last year. I couldn’t mention one artist or something that I would connect to, but for sure you can see references – like a year ago, I was very inspired by Larry Sultan and his book about his family, and I always liked the work of Carolyn Drake, and how she collaborated with her subjects.

How has the process of connecting with your own heritage been for you?

I discovered a lot and I really got the feeling that I got to know my grandmother even more than I knew her before, even though she’s really fading away and her memories are really disappearing. At the same time, the core of a person stays there. It helps me understand the whole family, and also my heritage. It really connected me to my landscape – the importance of the landscape where I grew up, where she grew up, how it all influences us.

If you could describe your own graduation work in three words, what would they be?

Memory, dementia, and family.

Is there one photo or reference that’s particularly important for you?

I think they’re all equally important. In the end, I feel really connected to my video work, because I feel it’s a bit less stylized, and it shows my personality even more, because it’s not technically perfect, and it really allowed me to show my intimate interactions with her.

What was the most fun thing about making this photography series?

I think going around Slovenia, and just exploring my country while really having all these conversations I had with my grandmother in mind and making these landscapes filled with my imagination. I wouldn’t say the most fun part, but the most fulfilling.

What’s the most important thing you’ve learned at KABK?

Through these years, I really managed to find my voice, and what kind of stories I want to work with. I decided to make a video, basically in the last semester, while I hadn’t done any video before. It’s nice that they make you realise that you have your visual language and within that it’s still possible to find new ways to express that. I had to go with my guts.

Yeah, but at this point, it’s not an uneducated guess anymore – it’s an educated one now! Good luck tomorrow.

Images by Matevz Cebasek

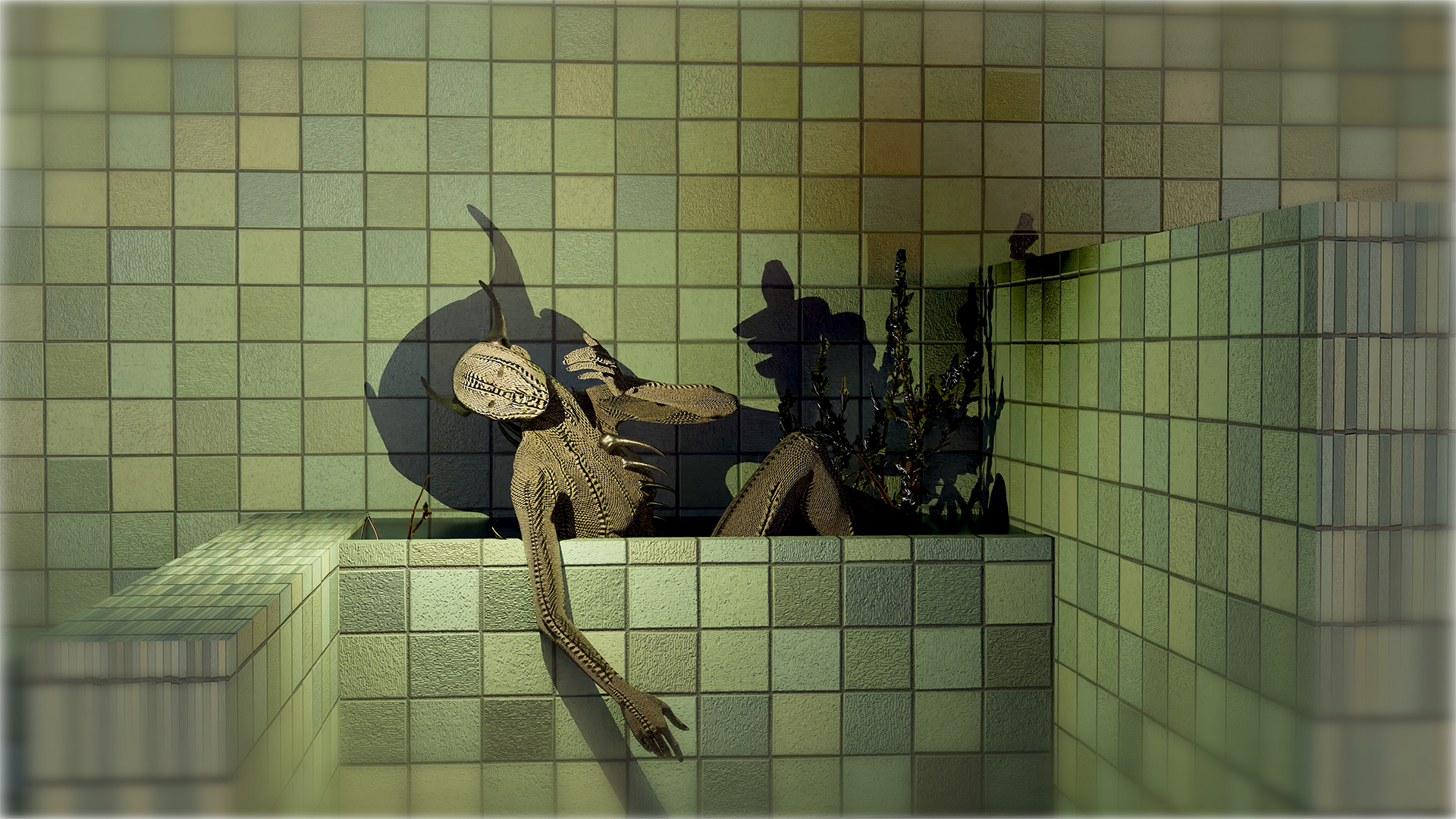

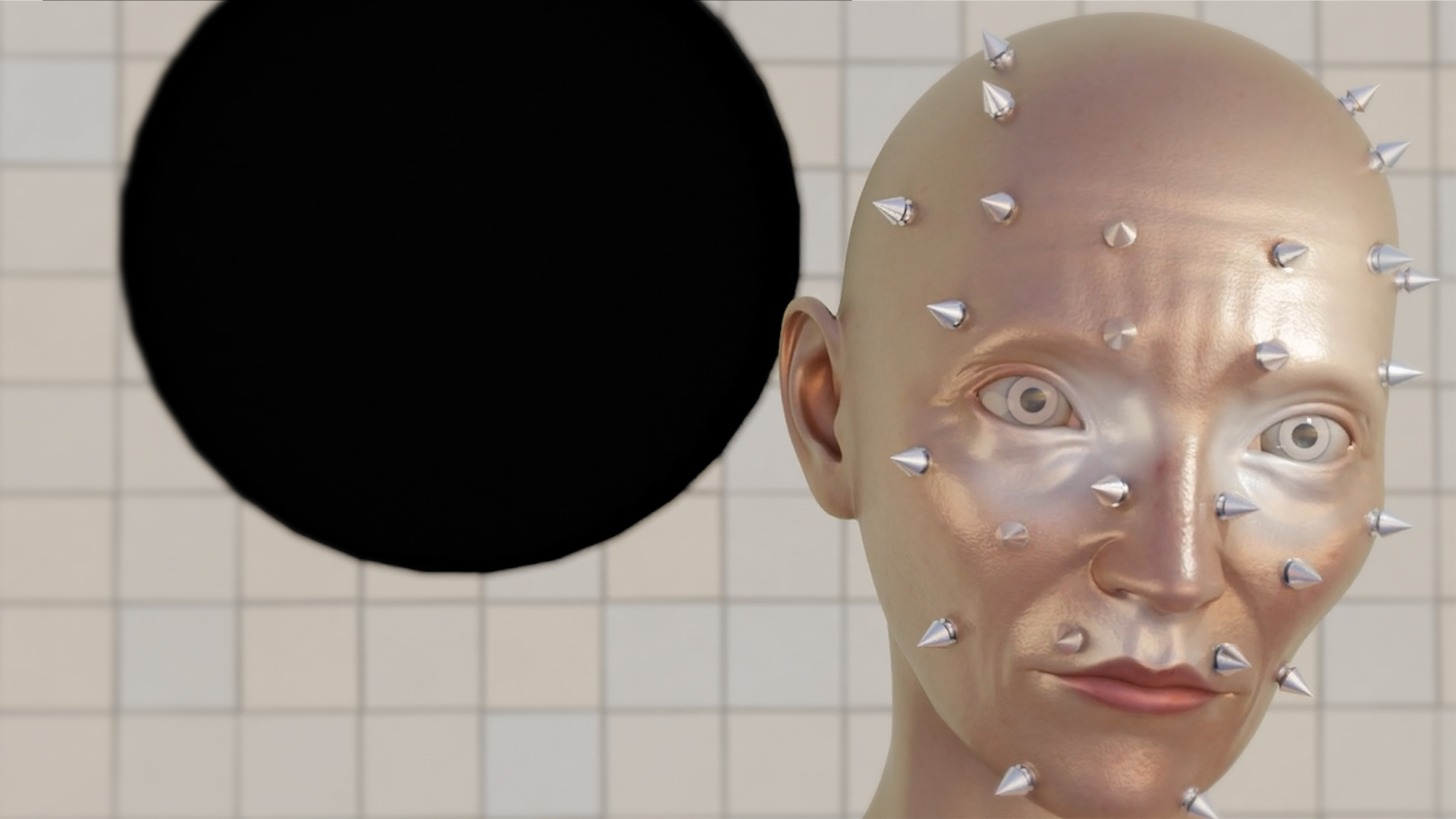

Meet Julie Goslinga, whose 3D-animated film installation boldly explores the concept of ‘Otherness’. Through themes of violence and sex , its connection to Queer identity, and a humorous self criticism this work invites the viewer to adjust their judgment of the strange. Through their unique approach, she challenges conventional expectations of artists and institutions, striving to communicate the complexities of sexual otherness without conforming to tokenism. Julie’s work is a profound exploration of beauty, discomfort, and the often-untouched corners of the sexual unconscious, all rendered through the meticulous medium of 3D digital art. Her dedication to pushing boundaries and inviting audiences to rethink their perceptions is a testament to her artistic vision and personal courage.

How’s your day going?

It’s quite intense, but it’s alright. I think that it’s so hot, it’s also not really helping everyone. Everyone, I feel like, just wants to be on the beach.

Same, wishing I was outside. I won’t keep you long. Can you tell me about the story behind your grad work?

Yes, so the final work, it has various states of being – right now it’s in an installation with two additional screens that sort of extend the universe. But the final work is a film. It very much has to do with exploring the unknown in sexuality and how that connects to your identity as a queer person. And I was very much focused on exploring the connection between violence and sex. To explain to others how it’s like to have this sense of sexual otherness, and expressing that without coming across as just arrogant or as some egocentric artist was a very hard thing for me to do. And so, I realised that my work really was creating this additional layer in which I criticised how we expect an artist to communicate and how an artist then is expected to communicate back. Sort of how the institution puts words in your mouth. And for me, I’ve always had difficulty with having to tokenise myself as queer for an audience within my art. So, I wouldn’t even describe this work as a queer work.

If you would describe your own work or your graduation work in three words what would the three words be?

Otherness, sexuality and identity.

Aesthetically speaking, how have you translated your story to be conveyed the best?

I only really work with 3D. What I like about 3D as a medium, and what I don’t like about it as well, is that there’s a lot of sources for things to be beautiful. So for things to be by a Western standard of beauty, especially with character creation. And when you’re talking about the sexual unconscious, you very often go into alien territories, monstrousness. In my visual language, I at least try to approach that the same way, where the scenes are beautiful and they’re dramatic and they’re baroque, but they’re also slightly off-putting, and there’s a creepy edge to them that is a bit inexplicable. I think when you go very deep into your sexual unconscious, or the parts of your sexual self that don’t fit into a daily conversation about who you slept with last week, you very often go into territory that’s either non-conforming, or slightly disgusting, or slightly off-putting. And I find that specific place very intriguing, where is the edge where we can still talk about a sexual encounter comfortably, and where does it become too far or too much? I’ve had reactions, where it’s just like, oh, this is really creepy, or I don’t like looking at this. And with other people, they say this is beautiful, and it touches me, and I recognize it. And that difference, I think, says so much also about how they encounter themselves and are in a connection with their own sexuality.

And why did you choose the medium of digital and 3D?

For me, it’s a very great tool to make films specifically, mostly, well, first of all, out of ease, because I can do it off my PC at home. And second, what I really like is when you work with a medium that is inherently so fake and tries to approach real life, or tries to recreate reality, it immediately creates a distance from the actual subject matter. And for me, that distance was quite important, because when you’re talking about such real, visceral things, but you’re putting it in a medium that only tries to approach reality, it gets a bit harder to understand, or it becomes harder for it to actually hit home. And with this specific project, I think that was quite essential to also mirror the way that the subject matter is already hard to understand.

Okay. So, obviously, these topics are also quite vulnerable and personal to talk about. How is it for you to talk about this openly and make work about this?

In a funny way, it’s actually quite natural. I’ve always been most curious about sex and sexuality, and that has always been a part of my identity. I think I also grew up privileged enough to be able to do that, and I’m very thankful for that. I feel like the way that I’m approaching it here is also inviting and beautiful and intriguing enough.

What do you hope your audience takes away from this artwork?

Maybe a different perspective on the strange or the slightly uncomfortable. I feel like I’ve sort of put it in a jacket that’s approachable, and I would love for people to take a sense of curiosity or intrigue, or to want to delve deeper into the specific topic of otherness and what it might mean to be strange or unapproachable.

And you’ve spoken about being a not-so-popular high-schooler to a digital creative pipeline. But how do you feel like that informs your decisions now?

I mean, I feel like high school is a very tough place for a lot of people, and I feel like that’s also the moment that everyone gets an otherness described to them. It’s like you always have this little club of weird people at the back of the class, and I feel like when you’re already in circles like that, it maybe keeps you home more, and then with the age of the Internet, you’re on the Internet more. I discovered 3D porn way earlier, and that was a really big intrigue at the time. I was always busy with writing my romance stories and not really as much with the rest of the class. I feel like that really influenced the capabilities I have now because I was already able to maybe discover a certain strangeness, but also because you’re already slightly being assigned an otherness, you’re less uncomfortable with exploring what that term might mean.

At the same time I think it’s difficult when you also assign yourself an otherness. It’s like,, you might not fit into the societal norm, but you’re also sort of shooting yourself in the foot by labeling yourself as other and withholding you from experiencing things with other people. So, it’s this very double thing where that did influence my creative life, but I think also for the longest time I was trying to make myself special out of a certain sense of needing to be special.

Being othered makes you not want to be like the ones othering you, but the deeper longing is maybe that they would have accepted you while having this special interest at the same time.

Yeah, deeply true, deeply true. This is also sometimes a problem I have especially in the queer community when we just embrace everything and don’t recognize it, you’re also excluding a conversation about difference. And difference is a natural thing that happens between everyone and norm is also not a static thing. So it’s maybe more ethical to just deeply encounter a person as they come to you and not ascribe that difference from the start.

Yeah, and I think there’s a really big thing of creating your own group where you do belong and then you get to other people like you were othered. And it’s like the bullied becoming bullies.

Yeah, you’re hitting it right on the nose because when you then try and it’s such logical human behavior but when you turn into the bully you’re reinforcing the norm that’s already there. You’re recreating it. I’ve been fantasizing about a version of the world where we can do that in a more ethical manner which I think… Well, I mean, the work as it is right now is quite pessimistic because I don’t believe that that’s possible. But I think for the future I would really delve deeper into the ethics of encountering and the ethics of othering and how that can be done in a way that works both politically but also personally. Facing your prejudice is an incredibly difficult thing to do but I think it’s so essential in becoming a human being or just being a human being.

So what’s the most fun thing about making this graduation work?

Seeing it be done. It’s very special to spend a lot of time with the subject and go through a lot of frustration and difficulty and I feel like it’s never really. But with the way that it’s turned out now, I’m satisfied to call it done. It’s been so incredible to birth something with the help of so many wonderful people and just have it become. I think a lot of art school is just trying to figure it out, and a lot of people throughout their lives are just trying to figure out what you want to bring or what you want to say, and it’s been absolutely orgasmic to find something to say. It’s such a privilege and I’m so deeply thankful for being able to finish this and I to get the space to talk about it, and to get opportunities like this to talk about it even more. The most important thing in this whole project is the privilege to speak.

What was the most important thing you learned at KABK?

I think that one of the most profound things that I learned here is that if you give people the space to surprise you in how they are as people and you don’t let your prejudice decide who they might be if you allow people to surprise you, you will be surprised. I think you can gain so much more from when you allow them to be not just their label.

Images by Julie Goslinga

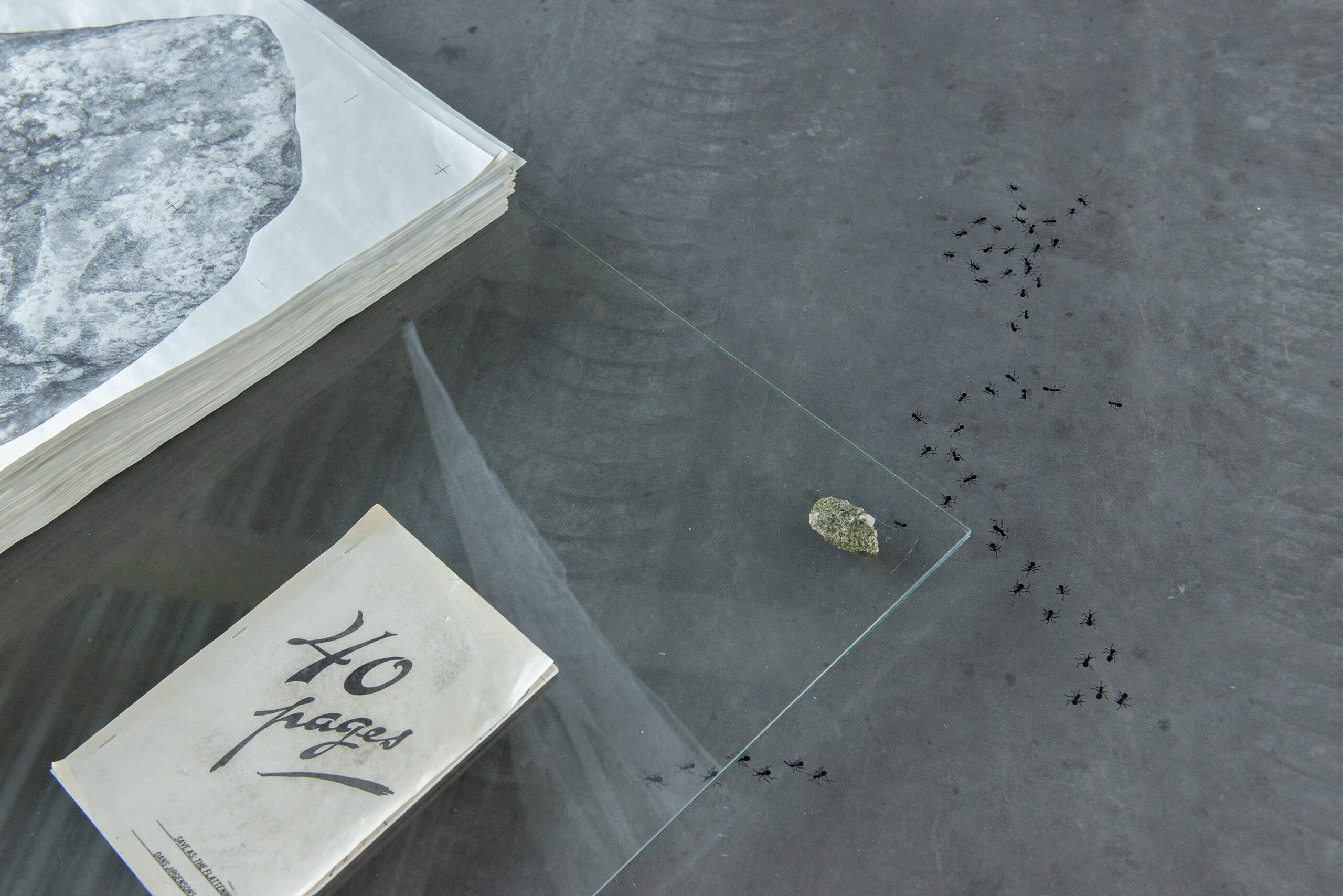

Dans Jirgensons’ work dives into the intricate processes of archiving and preservation. His graduation project is an exploration of how we document and immortalize objects and decaying material. Through innovative techniques and thoughtful execution, Dans challenges our perceptions of what it means to save, remember, and accumulate remnants of the past and present. Today, we’ll dive into the inspirations and methods behind his installation, and discover the stories woven into his art.

Hi Dans! Can you tell me about your graduation work?

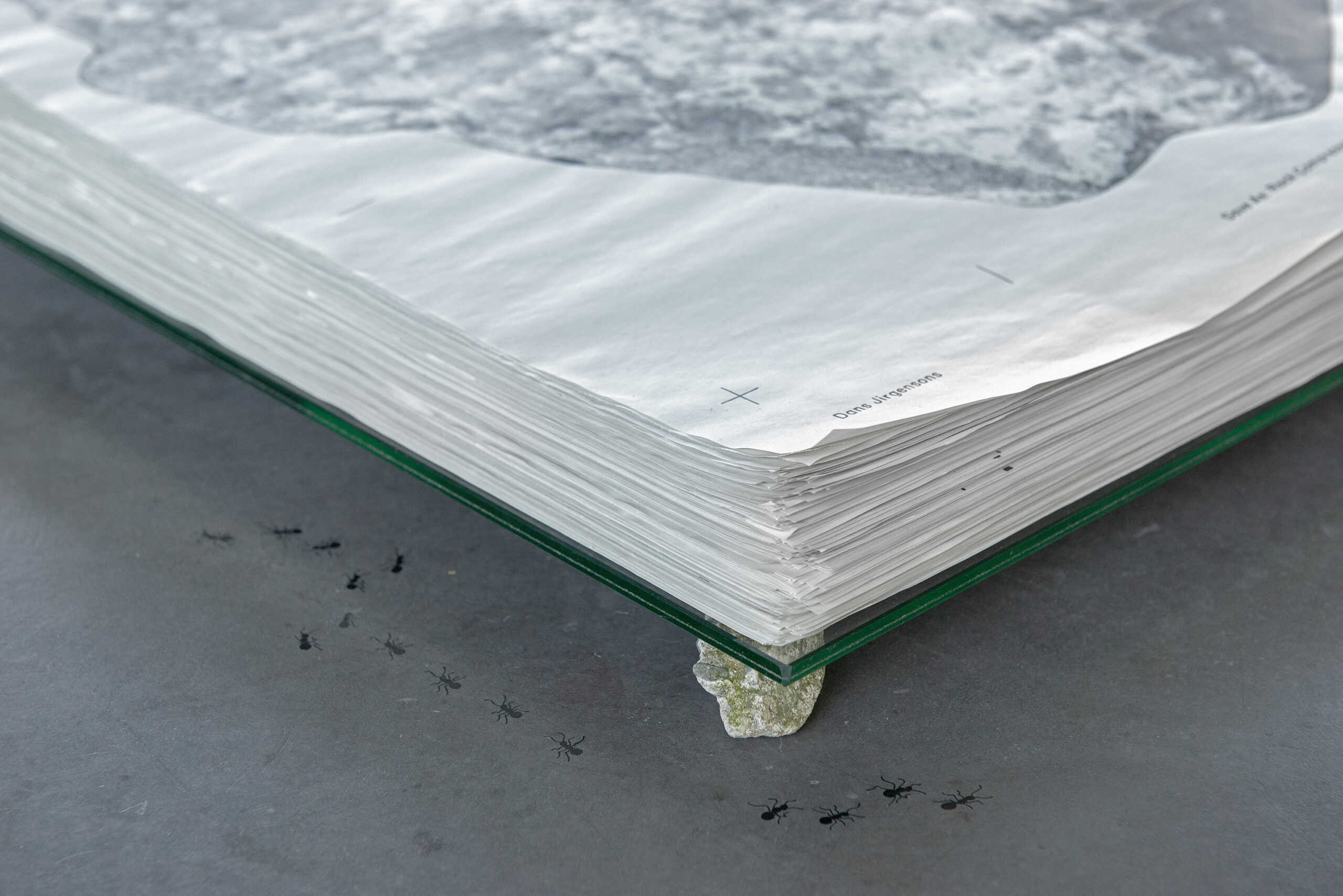

My installation is basically three attempts of archiving.The main piece, 3 by 2 meters, is a big frottage arrow. Frottage is this method of sketching over a relief and then getting like an imprint of something. And then there’s embalmed papers, inserted into epoxy, which is also a preservation or archiving material, and finally I have a big glass panel on the floor, with a stack of 500 posters, which is this archive of a rock that I found actually right in the public art courtyard, that I archived by screen printing it 500 times. Besides that there’s my process book.

What it is that you search for when making this body of work – are you interested in the techniques of archiving while it doesn’t really matter what it is that you’re archiving or are you archiving specific objects that are important to you?

I find specifically this question and the archiving method, are the main important parts to me. For example, this arrow matters to me, the archivist in this case, but it could also not matter to you. But what does matter to everybody is that it’s preserved and indexed in a system that can be replicated, et cetera.

Are you a hoarder?

I’m personally quite an archivist, I save a lot of things, but not just like a quick Pinterest thing – I keep track of things. I have an Are.na channel where I put pictures of colophons or books for future references. Maybe my camera roll is a big hoarding place, but the things that are archived, music or for example, these colophons don’t feel like hoarding – because they’re archived. I feel like not everybody has this sort of mindset. For my graduation project, I started wondering, like, why? The goal was to explain why we archive. I recently read a book about archiving, they were mentioning this problem about a lot of big archives, where there’s no love between the content and the archivist. So then to me, it feels very interesting to focus on the archiving lifestyle of some people who have love for their content.

So there is still always a choice you have to make between what you archive and what you don’t. How do you decide which ones deserve eternity and which ones are left to decay?

You cannot archive everything because that is hoarding. You don’t have the time to catalog everything and put it into a system. I looked into space archives where these disks that were sent into space archive the earth in a way. And after the first one was sent, people had problems with the choices that had been made, so they sent something new to space again. The way that the earth was presented on this second disc felt like a happy-go-lucky type of utopia, so there was an artist who sent even more pictures to space, including things of military and famine and that type of stuff. I feel like there will always be people after you and that doesn’t necessarily take away your responsibility for what you’re archiving. But, yeah, everything continues when you’re done as well.

So you’re giving yourself permission to not archive everything because people after you will also be archiving things.

Yeah, but also you can take into consideration who you’re archiving for. I think that would be the main aspect of deciding what gets to stay. Because I’m just archiving for myself, honestly. So then I have only myself and my storage space in mind.

Yeah, that’s your constraints. And how do you approach working with decaying materials?

Their fragility and also their state of urgency that they contain, intrigues me to archive them.

But the process of archiving can also change the object. So if you’re, for instance, talking about archiving a paper in epoxy so it doesn’t decay, it’s not the same object anymore because you will not be able to really take it out of the epoxy, right?

Yeah, I think those choices, I guess, are dependent on if it wasn’t in an archive, then it wouldn’t exist, so that’s what wins the battle, essentially.

And aesthetically speaking, how have you translated your story of archiving and wanting to document and keep these things alive?

For this big arrow, the frottage method really works because it just shows what is there… I can control some direction of the pencil or whatever, but besides that it just captures the object. Actually, even the layout of my process book has big, full, bleed-to-the-edges image with small captions. I took that from an old book that a Hungarian classmate of mine gave me about cemeteries from the 90s or something, and it has this specific style as well. I used all kinds of different papers. Some have stamps on them that I found from old books, and I feel it changes the feeling of material. This type of small knickknacks feel very interesting to me. And then if somebody’s interested, I love to explain any detail that I do.

It’s these ‘everyday’ graphic design expressions that can really give you an insight into daily life in the past, so this archive actually becomes even more interesting in the future. Exactly, for example, this arrow thing. I’ve been working with arrows as a symbol, since my second or third year. Rocks, I think, from second year, because I made big papier-mâché rocks for an exhibition. I feel with archiving things, or just gathering things, and then doing something with them, you can create such interesting connections. I was also very much into a project about UFO photography, and how also ambiguous they become, and after a while, if you have a row of them, and if you would place a fingerprint on it with a quick circle with a pen, it can also become part of this row of, or archive of UFO imagery, where a picture of stadium lights can also look as freaky as a staged UFO picture. And then in my thesis, I was looking into this space archive, for example, which very much thematically connects to what I was doing before, so I think I quite enjoy making these types of collections.

How has your upbringing influenced your collection, do you think?

In Latvia, there’s a lot of nature, my parents live in the countryside, like there’s no houses around at all… you can go hiking, maybe the rock interest comes from there. I have a very specific circle of friends back home, which are all, graphic designers or architects and we were just big fans about any graphic design before I became a graphic designer, so I think this, community feeling started back there, just noticing things on the street, or seeing how other artists do things and then trying to replicate them, fangirling about art and design.

For example, my mother teaches art for kids. My dad is a sound engineer, so that’s where the music archive part comes into play, because he’s also archiving a lot of music and records too. I also have a big Christian background. This also informs not necessarily my current morals, but it still left a mark on me. It was a very positive mark, but nonetheless, I still think about that sometimes. I came to understand patience a bit.

And what was the most fun thing about making this collection?

I think I think the most fun was that I was including a lot of my friends in the process.

I also learn about my friends while doing it. Creating things together, especially with people you trust, and can also do very obscure things kind of meticulously, creative, and also pragmatic at the same time.

Thank you so much for your time!

Images by Scott van Kampen Wieling

KABK Graduation Show

from 27th of June to 2nd of July

Free entrance

get your tickets here!

Campaign image by Caterina Santullo en Alessandro Lucarini

Words by Pykel van Latum